Everard (Demoor), Clémence (1865-?)

| Everard among her male fellow students, including Jules Bordet. About 1892. Source: Archives de l'ULB, Fonds iconographique. |

Physician. First woman to hold a Belgian degree in medicine, University of Brussels (1893). Born 4 December 1865. Date and place of death unknown. Wife of Jean Demoor.

Contents

Biography

Little is known about Everard's childhood. She probably grew up in Brussels. Her father Edouard Emmanuel Everard was, according to Everard's birth certificate, a merchant. [1] Everard's parents must have belonged to the wealthy middle class, among whom it was becoming increasingly common to educate daughters as well. In any case, Everard had certainly received a solid education, studying Latin and Greek. She would otherwise never have been able to make a bid for a university medical degree. Perhaps, like Bertha De Vriese, young Everard took lessons from a private teacher, or she went to school in one of the free institutes for girls' education that the city council had set up in 1864 in collaboration with the progressive pedagogue Gatti de Gamond. In the latter case, she possibly also went through the regents' school that Gatti had installed in 1880. That was the highest degree a woman could obtain at this time. To teach this section, Gatti had for the first time brought in professors from the University of Brussels. As a result, the jump to higher education for girls was suddenly not that great anymore.

Sometime in the mid-1880s, Everard enrolled in the medical course at the University of Brussels. At about the same time as her, Marie Derscheid and Sylvia Vanheerswynghels also enrolled. This happened perhaps without much difficulty. The university had hesitantly opened its doors to women some years earlier, in 1880, with Emma Leclerq, Marie Destrée and Louise Popelin. Not without difficulty, the three young women had managed to make this breach in the all-male science bastion of the academic world. The 1876 law, which they had invoked, may not have contained an explicit ban on women, but it hid the issue in a subjective twilight zone. [2]

For the faculty of medicine, however, it was the first time a woman had joined the study benches. Everard, Derscheid and Vanheerswynghels were the first young women to start medical school in Belgium ever. [3] Medicine was considered a heavy discipline and required a good knowledge of Greek and Latin. Most students had not been taught these languages in their education. They therefore opted for shorter studies, such as natural sciences or pharmacy. Moreover, at this time, it was not clear to women whether their doctor's degree could also get them jobs. The 1876 Act stipulated that the government would decide under what conditions women would be allowed to enter medical professions. [4] De facto, this meant prohibition. It was not until 1884 that Isala Van Diest, a general practitioner qualified abroad, forced a breakthrough. She had been running a gynaecological doctor's practice in Brussels for some time and obtained that her situation be legalised in a royal decree. It is possible that Isala Van Diest's precedent encouraged Everard in her choice.

Everard graduated as a doctor of medicine, surgery and midwifery on 16 March 1893. She was the first woman to receive this degree, moreover with brilliant distinction - great distinction (magna cum laude) - and this did not go unnoticed in the press. The Gazette de Charleroi wrote:

- "Un gros événement pour le monde féminin et féministe, et même pour le monde scientifique. Depuis jeudi matin, la Belgique possède une dame-médecin. Une jeune femme, Mlle Clémence Everard, a passé les examens du doctorat avec une grande distinction et a été proclamée docteur en médecine, chirurgie et accouchements [...] C'est une jeune femme de 26 ans, qui suivi les cours de l'Université de Bruxelles depuis sept ans et qui, avant aucun autre membre de son sexe, a vaincu les difficultés de cette longue période d'études."[5]

La Meuse and Le Peuple (18 March) also devoted a piece to the news event. The newspaper Indépendance Belge itself delivered an interpretative article on the "femme-médecin" phenomenon and paid Everard a visit, which it reported to its readers:

- "Nous lui avons rendu visite ce matin, en apprenant le résultat de son examen final. C'est une grande jeune fille brune, élancée, au teint pâle et mat, à l'oeil vif et bon, avec un sourire un peu grave. Elle portait le grand tablier-bavette en toile grise, des soeurs de charité et des internes d'hôpitaux. 'Les études de médecine sont bien longues, nous a-t-elle dit, mais je me suis faite à cette vie de travail, et maintenant je ne pourrais plus la quitter. J'aime à consoler les malheureux, d'alléger leurs souffrances. Les femmes et les petits enfants surtout m'inspirent de la pitié, et je veux dans la mesure de mes moyens travailler au soulagement de leurs maux. Mais, je vous en prie, ne dites pas tout cela: laissez-moi à ma vie simple.'"[6]

The way Everard describes her work here is peculiar: for her, medical practice seems to be a purely caring and comforting enterprise, born of a compassion for the weakest. There is seemingly no evidence of scholarly activity, fuelled by scientific curiosity, here, despite the fact that Everard did have research ambitions, as her subsequent career creates clear. In this way, the young doctor, perhaps consciously, gave the profession of medicine a 'feminine' interpretation. That she also appeared to wear a nurse's uniform and not a doctor's coat in the process is in keeping with the image evoked in her words.

Shortly after graduating, Everard went to work, presumably as an assistant, in Paul Héger's laboratory. At the same time, she opened a medical practice in Brussels. University assistants were in the habit of doing this, it provided extra income in addition to the poorly paid and temporary post of assistant. During her assistantship, Everard mainly conducted research on the behaviour of white blood cells in infection. Earlier, she had published a paper on this subject with her study companion and future husband Jean Demoor (1892). Demoor, like her, graduated as a doctor in 1893. A second publication the two assistants wrote together with the botanist Jean Massart (1893). The latter was a fellow student and former colleague of Demoor. [7] Everard also worked closely with Jules Bordet, who was a fellow student of hers. Like Everard, Bordet had started training as a doctor in 1886.

It seems that Everard gave up her research career and medical practice after her marriage to Demoor on 28 January 1895. Her marriage certificate records her as 'without occupation'. The Demoor family had a number of children, whose son Paul would follow in his parents' footsteps. From the sidelines, Everard watched her husband's blossoming career. In 1907, he succeeded Héger in the chair of physiology and was elected rector of the university in 1911. After her husband's death in 1941, Everard was left as a widow.

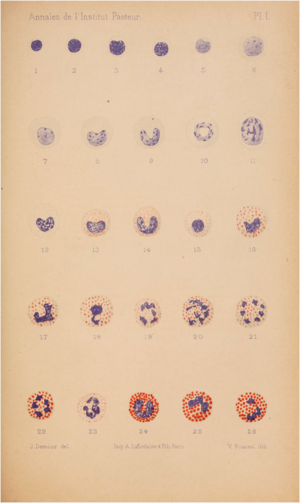

| Image from article: "Sur les modifications des leucocytes dans l'infection et dans l’immunisation", in: Annales de l'Institut Pasteur, nr. 2, 1893, 165-212.

|

Publications

- "Les modifications dans les globules blanc dans les maladies infectieuses", in: Annales et Bulletin de la Société royale des sciences médicales et naturelles de Bruxelles, (1892), 309-329. (Met Jean Demoor)

- "Sur les modifications des leucocytes dans l'infection et dans l’immunisation", in: Annales de l'Institut Pasteur, nr. 2, 1893, 165-212. (Met Jean Massart en Jean Demoor)

Bibliography

- Brabant, Burgerlijke Stand, 1582-1914, geboorteakte 5598, gedigitaliseerd op: Familysearch.org, geraadpleegd op 24/03/2017 (H. Bovens).

- Brussel, Burgerlijke stand, Overlijden 1894 oct-dec; Huwelijken 1895, gedigitaliseerd op Zoekakten.nl, geraadpleegd op 24/03/2017 (H. Bovens).

- "La première femme médecin", in: Gazette de Charleroi, 16 (1893), nr. 76, 17 maart, 2. (H. Bovens)

- "Au jour le jour. Echos de la Ville", in: L'Indépendance Belge, 64 (1893), nr. 76, 17 maart, 1. (H. Bovens)

- Gubin, Eliane en Piette, Valérie, Emma, Louise, Marie… L’Université Libre de Bruxelles et l’émancipation des femmes (1834-2000), Brussel, 2004, 94.

- Creese, Mary en Creese Thomas, Ladies in the Laboratory II: West European Women in Science, 1800-1900: A Survey of Their Contributions to Research, Maryland, 2004, 104.

- Keymolen, Denise, "Feminisme in België. De eerste vrouwelijke artsen (1873-1941)", in: Bijdragen en Mededelingen betreffende de Geschiedenis der Nederlanden, 90 (1975), 38-58.

- Demoor, Jean Henri, in: Biographie Nationale, 1977 175-192

- Bruynoghe, R., "Notice sur la vie et les travaux de M. J. Demoor, membre titulaire", in Bulletin de l'Académie Royale de Médecine de Belgique, (1941), 268-271.

Notes

- ↑ De Almanach de Bruxelles van 1895 vermeldt hem als een 'fabricant de fleurs et couronnes mortuaires, vannerie'. Almanachs de Bruxelles, Brussel, 1895, volume 1, Namen/Noms, 65. (met dank aan H. Bovens)

- ↑ Indeed, the law stated that the government would determine the conditions under which women would be admitted to university benches.

- ↑ Practising doctor Isala Van Diest had in fact obtained her medical doctorate in Switzerland. Since her degree was not compatible, she did take additional exams in obstetrics and surgery at the University of Brussels in 1882-83. However, apart from the maverick Van Diest, no woman had yet ventured into Belgian medical school.

- ↑ Law of 20 May 1876, art. 45: "Le gouvernement est autorisé à fixer les conditions d'après lesquelles les femmes pourront être admises à l'exercice de certaines branches de l'art de guérir." ["The government is authorised to lay down the conditions under which women may be admitted to the practice of certain branches of the medical profession."]

- ↑ "La première femme médecin", in: Gazette de Charleroi, 16 (1893), nr. 76, 17 maart, 2.

- Translation: " big event for the women's and feminist world, and even for the scientific world. Since Thursday morning, Belgium has a lady doctor. A young woman, Miss Clémence Everard, has passed the doctoral examinations with great distinction and has been proclaimed a doctor of medicine, surgery and childbirth [...] She is a young woman of 26, who has been attending the University of Brussels for seven years and who, before any other member of her sex, has overcome the difficulties of this long period of study."

- ↑ "Au jour le jour. Echos de la Ville", in: L'Indépendance Belge, 64 (1893), nr. 76, 17 maart, 1.

- Translation: ""We visited her this morning, on hearing the result of her final examination. She is a tall, slender, dark-haired girl with a pale, dull complexion, a keen, kindly eye, and a somewhat serious smile. She was wearing the large grey canvas apron of the Sisters of Charity and hospital interns. Medical studies are very long,' she said, 'but I got used to this life of work, and now I couldn't leave it. I like to console the unfortunate, to alleviate their suffering. Women and little children especially inspire me with pity, and I want to work to the best of my ability to relieve their suffering. But please do not say all this: leave me to my simple life."

- ↑ Massart and Demoor collaborated in 1892 in the laboratory of Leo Errera.