National Fund for Scientific Research (FNRS-NFWO)

In French: Fonds National de la Recherche Scientifique (FNRS)

In Dutch: Nationaal Fonds voor het Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek (NFWO)

Contents

History

Preamble

In the years following the First World War, an optimistic enthusiasm for science spread through Belgian society. Chemical warfare had not tainted science. On the contrary, science was seen as an instrument with which the war had been won and with which the country would now be rebuilt, more modern and better than before. The financial and industrial elite in particular turned to science. They were convinced that science could create prosperity, because the knowledge it generated could be used for industrial innovation. Until then, with the exception of the Fabrique Nationale de Herstal, the scientisation of Belgium's industrial sector had failed to materialise,[1] but a research dynamic could not be expected to emerge from industry itself.

The demand of industrialists for academic scientific input coincided with the growing need of Belgian university institutions for financial resources. Investment in the scientific infrastructure of higher education had already been on the meagre side before the war. After the war, all universities, especially the free institutions, lacked the material infrastructure and financial resources needed to carry out high-level research, especially in the new experimental research. A cooperation between the academic and industrial worlds emerged, which was crowned in 1928 by the foundation of a real investment fund for fundamental research: the National Fund for Scientific Research. The initiators were the members of the University Foundation, founded in 1919. The Belgian elite thus followed in the footsteps of other countries, where the private sector had long been involved in scientific patronage.[2]

| Francqui was a leading figure in the CRB, the University Foundation and the NFWO/FRNS. |

The Founding

The founding of the NFWO/FNRS was supported by the burgeoning economic boom of the late 1920s, but also by the striking personality of King Albert I, who emerged as the godfather of the movement for private investment in fundamental science. In October 1927, during the jubilee celebrations of the Cockerill factory in Seraing, the monarch gave a speech that attracted a great deal of attention, symbolising the start of industrial scientific patronage. He drew the attention of his audience, all representatives of industry and banking, to the poor situation of academic research institutes and the impotence of the already heavily burdened government. Fundamental science - "science pure" - as it was practised in the academic world, was nevertheless the absolute condition for the emergence of applied science, according to the King.

Some two months later, on 26 November 1927, the illuminated patron repeated his appeal in the Palace of the Academies. Emile Francqui, as President of the University Foundation, presided over the formal session. On the podium were professors, academics and the directors of the country's major scientific institutions. In the hall were government representatives, ministers and the cream of Belgian banking and industry, including philanthropist and scientific patron Armand Solvay.

"Créatrice de richesse, la science est pauvre elle-même. Il faut venir à son aide."[3] The monarch's winged words made an impression once again. Three months later, a special Propaganda Committee led by Emile Francqui had already collected 100 million francs, including donations from leading banks and companies, large and small gifts from individuals and a sum of 25 million francs from the Solvay family. One month later, on 27 April 1928, the Fonds National de la Recherche Scientifique/Nationaal Fonds voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek was created.

Statutes and Organisation

| Honorary medal with the head of Jean Willems, 1970. Copyright © STAM. |

The newly established fund, chaired by Francqui, consisted of a board of directors of 26 members from industrial, financial and academic circles, including the rectors of all higher education institutions. There was also a bureau and a Finance Committee. In its statutes, the FNRS/NFWO undertook to support and encourage scientific research in Belgium. In this sense, it partially took over the torch from the University Foundation. The NFWO/FNRS aimed to provide individual scientists with financial and logistical means, by granting mandates, credits for trips and congresses and the provision of scientific instruments.

The statutes of the new fund emphasised the apolitical, philosophical and linguistically neutral character of the association. The first board of directors was an emanation of this principle. The twenty-six members represented in a balanced way the universities and institutes of higher education, the academies, the industrial and financial sector. The Belgian state was not represented. The composition of the board of the NFWO was thus, just like its foundation, a private affair between the monarch, top people from the industry and banking sector and a number of prominent academics. In this way, the fund formed a regulated framework within which academic scholars and top industrial and banking figures could meet. In 1930, the government passed a bill exempting donations to the NFWO from taxation, in line with the American donation regulations.

The members of the board of directors stipulated that the fund would focus on fundamental and pure science. Over time, this policy line caused frustration among some industrialists who had envisaged a more pragmatic approach for the NFWO. Therefore, a Special Bureau Science-Industry was established in 1929 by the NFWO in cooperation with the Commission mixte science-industry, to subsidise industrial research. The bureau received a small part of its funds from the NFWO.

Evolution

During the Second World War, the NFWO/FNRS remained in post, albeit in a reduced capacity. In 1943, it set up a university helpdesk to meet the acute shortage of resources that researchers were experiencing. There was also an increase in the number of exchange mandates with Germany. Because the management council had to be attended by two members of the occupying power, meetings were kept to a minimum.

In 1947, the Interuniversity Institute for Nuclear Physics (called the Interuniversity Institute for Nuclear Science from 1951) was founded. This was a de facto association under the leadership of the NFWO director Jean Willems and Marc de Hemptinne. This institution supported fundamental research but also more application-oriented research in the field of nuclear sciences. In 1958, the NFWO, together with the Ministry of Health, established the Fund for Medical Scientific Research (FGWO/FRSM). This fund formed a separate part of the NFWO and was responsible for the distribution of finances to research projects in the medical sciences, where there was a pressing lack of resources. Finally, in 1965, the Fund for Collective Fundamental Research was established. This fund was responsible for financing research projects in all fields of science, except for the medical and nuclear sciences.

The communitarian tensions of the 1960s in Belgium, particularly at the universities of Leuven and Brussels, had a major impact on the structure of the NFWO/FNRS, which was considered a predominantly French-speaking bastion. Critics are aware of the perceived Flemish backwardness in scientific research at the FNRS/NFWO. Consequently, in 1970, the fund's budget and government subsidies were divided up by language community. The tone was set for a further breakdown of the Fund's structure. In 1992, new statutes were drawn up that split the Fund into two de facto autonomous institutions, one Dutch-speaking and one French-speaking. The final split into two separate institutions followed in 2005, the FWO-Vlaanderen and the F.R.S.-FNRS.

Projects

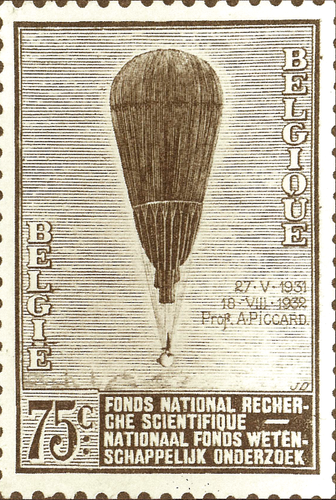

| Piccard's stratospheric flight in the FNRS-1 was one of the NFWO's prestige projects. |

From its inception, the NFWO/FNRS has played an important role in awarding fellowships for doctoral research. The individual research of researchers, such as that of Nobel Prize winners Corneel Heymans and Jules Bordet, was also supported with a sometimes decades-long subsidy, while Paul Bordet received a defined subsidy for research into blood serum. With the democratisation of higher education, followed by the law on university expansion in 1965, the number of grant applications, especially from doctoral students, rapidly increased.

Soon, however, the NFWO/FNRS launched itself into delineated research projects, which were often spectacular. In the inter-war period, funding went mainly to projects that were useful, innovative and peaceful, and that could put Belgium on the map as a country or enrich the nation. The first project took place in 1930, when under the leadership of archaeologist Fernand Mayence of the Royal Museums of Art and History, and with the financial support of the FNRS/NFWO, a Roman metropolis was excavated in Syria. In later years, too, archaeologists found support in the NFWO/FNRS, for example in the excavation of Alba Fucens in Italy and prehistoric sites in Iran. Finds were transported to the Royal Cinquantenaire Museum. New, equally prestigious projects quickly followed, such as the imaginative stratospheric flights of physics professor Auguste Piccard in his balloon the FNRS-1 (1931) and his deep-sea experiments with the very first bathyscope ever, the FNRS-2.

| Drawing of the first, in Belgium developed, electrical calculator, 1955. Source: NFWO/FNRS. |

The establishment of the International Research Station at Jungfraujoch in 1931 and the expedition to the Easter Islands (1934) may not have been commercially useful, but the scientific exploration of the Ruwenzori Massif in 1932, the hydrobiological and piscicological research of Lake Tanganyika in 1946 and the construction of a helicopter by Nicolas Florine (1933) certainly were.

After the Second World War, 'Big Science' saw the light of day, a collective and internationally oriented scientific practice with leading roles for space sciences and nuclear physics. The NFWO/FNRS was also involved: in 1945 it set up a committee to study the scientific branch of nuclear physics. In the 1960s and 1970s, it provided support for the establishment and equipping of the new Laboratory for Nuclear Physics at Ghent University. Scholars could also count on support for the purchase and design of increasingly large scientific apparatus, intended for the exploitation of 'big data'. In 1955, the FNRS/NFWO became the owner of a gigantic electronic calculator, the very first to be designed in Belgium. As of 1950 the NFWO also financed the research into the development of the electron microscope in the Centre for Electron Microscopy.

| The expedition to the Great Barrier Reef yielded many natural treasures for Belgium. Source: Motty, via Wikimedia Commons. |

of Gaston Vandermeerssche of Ghent, the Leuven professor Joseph Lauweryns and the Brussels professor Luc Bouwens. The Ghent Digital Computing Centre was supported by the NFWO in the 1960s with repeated grants. In 1974 the NFWO participated in the creation of the European Science Foundation. The high costs of this type of research meant that the NFWO had to be selective. After all, distributing credits for the same research between different universities was a waste of money. In this way, the fund gradually oriented Belgian science and contributed to the specialisation and collectivisation of university research. As always, more 'classic' projects were also carried out, such as Gaston de Gerlache's South Pole expedition, the mapping of the Galapagos Islands, the expedition to the Great Barrier Reef led by Marcel Dubuisson, and the geomorphological and geochronological studies of the Quaternary at the VUB.

After the division into a French-speaking and a Dutch-speaking fund from 1970 onwards, each focused on research projects and mandates in its own language area.

Seat

The NFWO/FNRS (FWO-Vlaanderen, F.R.S – FNRS) has been located on rue Egmont in Brussels, where it occupies several buildings.

Finances

In the first ten years of its existence, the NFWO gave almost 45 million francs in support of science. Most of the subsidies went to support aspirants, associates and researchers. Until 1947, the FNRS/NFWO relied entirely on donations from the private sector. From then on, the government also stepped in with a generous annual subsidy, which thus became the most important source of income. In the course of time, the Fund was increasingly able to rely on interest from acquired capital. This source of income became the most important in the post-war period, while government subsidies also caught up with the increasing number of mandate and project applications. On the French-speaking side, the television show Télévie has been an important source of income since 1989 and remains so to this day. It relies on donations from private individuals.

Bibliography

- Werkzaamheid van het Nationaal Fonds voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek gedurende het academisch jaar 1928-1929. Overzicht, Brussel, 1929.

- De wetenschap ten dienste 1927-1952, Brussel, 1953.

- Balthazar,Herman, "Wetenschappelijk onderzoek en maatschappij. Een evolutieschets van het N.F.W.O 1928-1978", in: N.F.W.O. 1928-1978, s.l., s.d.

- Bertrams, Kenneth, Universités et entreprises. Milieux académiques et industriels en Belgique 1880-1970, Brussel, 2006.

- Bertrams, Kenneth, "Beyond academic science: Hoover and Franqui’s legacy in post-war Belgium", in: Remembering Herbert Hoover and the Commission for Relief in Belgium, Brussel, 2006.

- Bertrams, Kenneth, "Converting Academic Expertise into Industrial Innovation: University-based Research at Solvay and Gevaert, 1900-1970", in: Entreprise and society, 8 (2007), nr. 4, 807-841.

- Bertrams, Kenneth, Biémont, Émile, Van Tiggelen, Brigitte en Vanpaemel, Geert (red.), Pour une histoire de la politique scientifique en Europe (IXIe-XXe siècles), Brussel, 2007.

- Halleux Robert en Xhayet, Geneviève, La liberté de chercher : Histoire du Fonds national de la recherche scientifique, Luik, 2007.

- Geschiedenis van het FWO, website, geraadpleegd op 20/03/2018.

- Maillard, Cathérine, "Quelques projets historiques, financés par le FNRS", in: FNRS News, 94 (2013), september, 14-15.

- Diser, Lyvia, Wetenschap op de proef, Leuven, 2016.

Notes

- ↑ In neighbouring countries a scientisation of industry had begun. Significant examples are Electric and AT&T in the United States of America and the German Kodak, Siemens and AEG.

- ↑ Similar institutions, public and private enterprises and consultancies for the promotion of science, arose throughout post-war Europe. For example, in 1915 the British government established an Advisory Council for Scientific Research, the United States followed with a National Research Council and in France the Académie des Sciences was made responsible for organising experimental research with applications in industry.

- ↑ [Creator of richess, science herself is poor. We need to come to its aid.]