Massart, Jean Baptiste (1865-1925)

Botanist, born on 7 March 1865 in Etterbeek and died on 16 August 1925 in Houx.

Massart was officially called 'Massar'.[1].

Contents

[hide]Biography

Early life and education

Massart grew up in Etterbeek, in and around his parents' small houseplant nursery. The family belonged to the modest middle class. The young Massart attended secondary school at the local community college. Through the mediation of one of his teachers, however, he was able to transfer to an upper year of the humanities at St Michael's College (now Sint-Jan Bergmans College). With his knowledge of Latin and Greek in his pocket, he was then able to enrol at the Faculty of Sciences of the University of Brussels without any problem. At that moment he was just fifteen years old. However, the unexpected early death of his father forced the brand-new student to abandon his studies and take over the family business. His outlet during this period was a self-made little home laboratory, where he carried out microscopic observations and small experiments. After several years at the head of the family business, Massart followed the advice of a family friend and decided in 1884 to resume his studies after all. Meanwhile, he remained active in the family business. In 1887, he obtained a doctorate in natural sciences, specialising in botany.

Pre-war career: professor, conservator and explorer

After obtaining his doctorate, Massart immediately entered a new study programme, this time at the Faculty of Medicine. His second doctorate followed in 1891. After this, he joined the Faculty of Medicine as an assistant for one year. In 1892, Professor Leo Errera asked him to assist in his research and teaching. In Errera's Institut Botanique, Massart was in charge of practical exercises and supervision of researchers for three years. After this, he was a repetiteur for two more years. In 1897, the Brussels university administration promoted Massart to full professor.

From the beginning of his career, Massart's botanical research focused on plant geography. Unlike research on Belgian flora, this study of the geographical distribution of crops, the composition and definition of the various Belgian floral regions (vegetations) was still in its early stages. Moreover, Massart preferred the wild to the well-equipped laboratories of the Institut Botanique as a site of research and study. The young explorer thus belonged to a new breed of natural scientists who argued, now again, that biological laboratory study could not be complete without fieldwork.

[2]

Massart also attached importance to fieldwork in his teaching. Every fortnight, he and his students - including Josephine Wéry - undertook a collecting expedition in a particular region of the country.

[3]

Massart brought the laboratory to the field: together with his former fellow student and colleague Auguste Lameere, he put together a mobile laboratory kit for the university, with which they travelled all over the country. The photographic camera was also an important tool in their research.

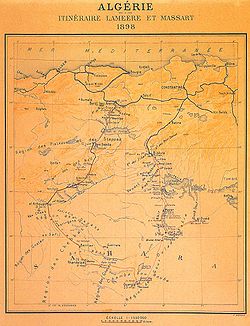

Lameere was also Massart's main companion on excursions abroad. In the summer of 1897, the two scientists toured the Swiss Valais Alps. They compiled their findings on the local fauna and flora in La dissémination des plantes alpines (1898). A trip to the Sahara, again in the company of Lameere, followed in 1898. Massart wrote down his climatological and biogeographical observations in Un voyage botanique du Sahara (1898). Wanting to broaden his scientific horizons further, the young professor then embarked as a doctor aboard a ship bringing back Muslim pilgrims from Djeddah to Indonesia. He penned down his account in Medecin pour hadji (1896). In Java, he spent some time at the Buitenzorg laboratory and undertook a botanical collecting expedition. He transferred the rich harvest of plant samples to the National Botanical Garden and the Botanical Institute of the University of Brussels.

[4]

Massart would continue to travel throughout his life. As late as 1922, he travelled to Brazil with Raymond Bouillenne, Paul Brien, Paul Vincent Ledoux and Albert Edouard Navez to collect botanical material, among other things. The results of this trip were published in: Une mission biologique au Brésil (1929). Immediately afterwards, he accepted invitations from American universities to travel around the United States and meet various scientists.

Because the financial resources of the university of Brussels were very limited, Massart took up the position of curator at the State Botanic Garden in addition to his professorship from 1902. There, he was responsible for the outdoor gardens, the cold greenhouses and the orangery. He also established a number of research stations in Belgium, including in Francorchamps and Koksijde. Here, local plant species were studied and compared. This was another way of bringing the laboratory to the field. In 1905, upon Errera's death, Massart took over his courses. He was also appointed director of the Botanical Institute. The workload forced him to quit his second post, at the Botanical Garden.

The Great War: resistance and escape

During the First World War, Massart ceased his scientific work because he felt he could not remain on the sidelines. His bitter indignation at the occupation was intensified when fellow German scientists published their manifesto Aufruf an die Kulturwelt in October 1914. Massart began building an extensive collection of German documents and propaganda texts to prove the mendacity and cruelty of the occupier. In early July 1915, this got him into trouble. He fled and managed to use false papers to get himself, his wife, children and his source collection out of the country, to the Netherlands. Via England, the family finally ended up in France, settling in Antibes. During that period, Massart worked at the laboratory of agronomist Georges Poirault. There, he mainly studied seasonal differences and their influence on the flora of the Cote d'Azur and Belgium, especially germination. He also taught courses at the Paris Museum of Natural History and taught free English at the local college. He also collaborated with the Belgian clandestine press. He wrote several pamphlets including: Comment les Belges résistent à la domination allemande (1916) and Le chiffon de papier (1917). Meanwhile, the family home was constantly open to frontline nurses who wanted to catch their breath.

After the armistice, Massart returned to the University of Brussels, resuming his botanical observations. In particular, he studied the fascinating recovery of nature in the hard-hit region around the Yser, where he believed he could see the struggle for life unfolding in all its ferocity. For this purpose, the biologist installed a laboratory in Nieuwpoort. He compiled the results of his research and observations in the publication La Biologie des Inondations de l'Yser et la flore des ruines de Nieuport (1920). He also established an experimental garden for the ULB at Auderghem in the Sonian Forest. This garden, named 'Jardin botanique expérimental Jean Massart', was unfinished at the time of his death. The garden still exists today.

Massart was elected corresponding member of the Académie royale des Sciences, des Lettres et des Beaux-Arts de Belgique on 4 June 1904 and effective member on 10 June 1911. In 1925, he was elected director of the Class of Sciences. He also served on the administrative council of the society Les Naturalistes belges. He was also a member and, for a time, president of the Société royale de botanique de Belgique. He was laureate of the Decennial Prize of the Belgian Government for Botanical Sciences for the period 1899-1908.

Nature advocacy

It was probably under the influence of his intense biogeographical research and his focus on fieldwork that Massart developed a particular commitment to nature. As early as the 1890s, he advocated the protection of nature. At this time, Belgium was among the most industrialised and urbanised countries in the world. Green space was under increasing pressure. Criticism of these pernicious developments came mainly from artistic and literary intellectual circles. Representatives of these groups sometimes aired a particular complaint into the parliamentary hemisphere through local representatives. In the early 20th century, an increasing number of Belgian biologists, including Charles Bommer and Léon Frédéricq, also entered the debate, albeit with their own scientific pleas. In doing so, they pointed above all to the crucial importance of pristine nature for their research. Without it, knowledge acquisition was impossible, they said.

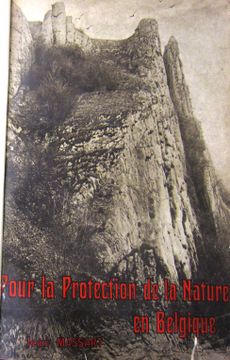

Massart was thus not the only one to make a stand for nature in this time period. However, he was the first to outline a concrete and realistic programme for nature protection in Belgium, which moreover transcended the local level. The establishment of different types of nature reserves in various regions of the country was Massart's most remarkable demand in this regard. In doing so, he was inspired by the campaigns for the establishment of national parks in other countries, such as the United States in the 1870s. This proposal was, among others, formulated in the richly illustrated Pour la protection de la nature (1912) byt the scientist-activist Massart. [5] Following this publication, Massart, in a lecture to the Class of Sciences at the Academy, called on his colleagues to denounce the loss of natural areas for research. Moreover, in 1912 he founded the Ligue belge pour la protection de la nature, which was joined by his friend Lameere, Hector Leboucq and Frédéricq, among others. Later, Massart also made important contributions to Belgian and international nature conservation. From 1912, for instance, he served for a time on the Landscapes sections of the Royal Commission on Monuments. [6] In 1921, the ecologist avant la lettre launched another large-scale appeal to members of the Touring Club de Belgique and the Société royale de botanique de Belgique to submit proposals for nature reserves to be created to the Commission on Monuments. Despite repeated calls, a first nature reserve in Belgium did not materialise until 1957.

Works

Massart has quite a few publications on a variety of topics to his credit. Early in his career, his main focus was on physiology and pathology. Among other things, Massart conducted research on the flow of white blood cells through blood vessel walls. [7] After joining the Botanical Institute at the University of Brussels, Massart refocused on botany. Together with Errera, Massart underlined the importance of mutations in the evolutionary mechanism. [8]

Central to Massart's botanical research was the systematic mapping of Belgian vegetation. Together with his botanical garden colleague Bommer, he published the two-volume Les aspects de la végétation en Belgique (1908 and 1912), a work containing numerous large-format photographs and plates. [9] It was mainly the coastal regions and alluvial plains that peaked Massart's scientific interest. He published the contribution Biologie de la végétation du littoral belge on this subject as early as 1893. Finally, in 1910, on the occasion of the Third International Botanical Congress, Massart published his synthesis work Esquisse de la Géographie botanique de la Belgique. In it, he described the distribution of vegetation in our country as a function of factors such as environment, soil and climate.

Among his works published at the National Botanical Garden is his Notice sur la serre des plantes grasses au Jardin botanique de l'Etat.

Science sociology

Together with socialist politician Emile Vandervelde, Massart researched "organic" and "social" parasitism. [10] He wrote further on the subject with Jean Demoor and Vandervelde in 1897: L'evolution régressive en biologie et en sociologie. The book was an attempt to apply biological laws to social evolution. Their thesis was that society is an organism and the organism is a cellular state. [11]

Nature protection

Massart was (one of) the first Belgian scientist(s) to advocate conservation from the mid-1890s onwards. In 1895-6, he did so in a note on the Javanese forests. [12] This was followed in 1912 by his “Protection de la nature”, published on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the Société royale de botanique de Belgique, in which he advocated, among other things, the creation of nature reserves. In the work, Massart, based on the scientific research on vegetation he had carried out over the years, listed 75 natural sites that he believed should be protected. In doing so, he paid attention not only to botanically valuable sites, but also to zoologically, geographically, geologically and archaeologically unique or representative areas. However, the many picturesque or monumental landscape photos in the work show that for the author, aesthetic pleasures played a role in his plea in addition to scientific arguments. Nature was a living monument, as well as a witness to the past. [13] In his publication, Massart also proposed a number of simple measures, such as banning the cutting of sods for burning, restricting the draining of marshy land and making the extermination of endangered species such as the raven a criminal offence. Massart's book became a reference point for Belgian "nature activist" scientists in the following decades.

Courses

Between 1922 and 1924, Massart published Eléments de Biologie Générale et de Botanique, an illustrated synthesis of his courses taught in the preparatory candidatures of medicine and physics.

Educational publications

The professor also published the work Un jardin botanique pour les écoles moyennes, in which he defended the importance of creating a botanical garden in schools. He described the most essential plants for such a botanical garden.

Publications

- A list with his publications can be found in: Marchal, E., "Jean Massart", in: Annuaire ARB, 141-158.

A large amount of publications and also some letters by Massart can be consulted online via the Lib.Ugent catalogue (consulted on 03/08/2023).

Bibliography

- Etterbeek, Burgerlijke stand, Geb., Afk., Huw., Ovl. 1861-1865, akte 39, gedigitaliseerd op Zoekakten.nl, geraadpleegd op 16/01/2018 (met dank aan H. Bovens).

- "Le patriotisme d'un savant belge", in: Le Belge indépendant, s.n. 1919, 25 januari, geraadpleegd op 7/08/2018.

- Brussel, Burgerlijke stand, Huwelijken jan-maart, jul... Geboorten jan-maart 1898, akte 2063, gedigitaliseerd op Familysearch.org, geraadpleegd op 16/01/2018 (met dank aan H. Bovens).

- Marchal, E., "Jean Massart", in: Annuaire ARB, 1927, Brussel, 69-140.

- Marchal, E., "Jean Massart 1865-1925", in: Bulletin de la Société Royale de Botanique de Belgique, 59 (1926), nr. 1, 7-10.

- Stockmans, François, "Jean Massart", in: Biographie Nationale, vol. 38, 561-569.

- Stockmans, François, "Jean Massart", in: Florilège des sciences en Belgique, 1968, 705-726.

- Raf de Bont en Rajesh Heynickx, "Landscapes of nostalgia: Biologists and Literary Intellectuals Protecting Belgium's 'Wilderness'", in: Environment and History, 18 (2012), nr. 2 , 237-260.

- Denaeyer-De Smet, Simone (e.a.), "Jean Massart: Pionnier de la conservation de la nature en Belgique", in: Dan Gafta en John Akeroyd (red.), Nature conservation: Concepts and practices, Berlijn, 2006, 26-45.

- Notteboom, Bruno, "De verborgen ideologie van Jean Massart. Vertogen over landschap en (anti)stedelijkheid in België in het begin van de twintigste eeuw", in: Tijdschrift voor stadsgeschiedenis, 1 (2006), 51-68.

- Stynen, Andreas, "Vaderlandse weelde op de kaart gezet. Belgische botanici, wetenschappelijke ijver en nationale motieven", in: Bijdragen en mededelingen betreffende de Geschiedenis der Nederlanden, 121 (2006), 680-710.

Notes

- Jump up ↑ The spelling 'Massar' is used on his birth certificate and marriage certificate. However, he signed the latter himself with 'Massart'. Jean-Baptiste's father also wrote 'Massar'. With thanks to H. Bovens

- Jump up ↑ Robert Kohler, Landscapes and labscapes. Exploring the lab-field border in biology, Chicago, 2002, 23-59.

- Jump up ↑ Wéry compiled their observations in the report Excursions scientifiques (Géographie, géologie, botanique et zoologie) organisées par l'extension de l'Université libre de Bruxelles et dirigées par M. le professeur Jean Massart, Brussel, 1908 & 1913.

- Jump up ↑ Poncelet, Marc & Nicolaï, Henri & Delhal, Jacques & Symoens, Jean-Jacques, "De overzeese wetenschappen", In:Robert Halleux, Geert Vanpaemel, Jan Vandersmissen en Andrée Despy-Meyer (red.), Geschiedenis van de wetenschappen in België 1815-2000, Brussel: Dexia, 2001, vol. 2, p. 263.

- Jump up ↑ Lawalrée, André, "De plantkunde", in: Robert Halleux, Geert Vanpaemel, Jan Vandersmissen en Andrée Despy-Meyer (red.), Geschiedenis van de wetenschappen in België 1815-2000, Brussel: Dexia, 2001, vol. 2, 250.

- Jump up ↑ Raf de Bont en Rajesh Heynickx, "Landscapes of nostalgia: Biologists and Literary Intellectuals Protecting Belgium's 'Wilderness'", in: Environment and History, 18 (2012), nr. 2 , 237-260.

- Jump up ↑ Halleux, Robert, "Naar de kern van het leven: de biologie", in: Robert Halleux, Geert Vanpaemel, Jan Vandersmissen en Andrée Despy-Meyer (red.), Geschiedenis van de wetenschappen in België 1815-2000, Brussel: Dexia/La Renaissance du livre, 2001, vol. 1, p. 298.

- Jump up ↑ Exhibition folder, "De evolutietheorie van Darwin, de sensatie van de 19de eeuw", "Darwin in de collecties van de Koninklijke Bibliotheek", georganiseerd door het Nationaal Centrum voor de geschiedenis van de Wetenschap, 19.

- Jump up ↑ Part 1 can be consulted on line on Lib.Ugent. Lawalrée, André, "De plantkunde", in: Robert Halleux, Geert Vanpaemel, Jan Vandersmissen en Andrée Despy-Meyer (red.), Geschiedenis van de wetenschappen in België 1815-2000, Brussel: Dexia, 2001, vol. 2, 250.

- Jump up ↑ Wils, Kaat, "De sociologie", in Robert Halleux, Geert Vanpaemel, Jan Vandersmissen en Andrée Despy-Meyer (red.), Geschiedenis van de wetenschappen in België 1815-2000, Brussel: Dexia/La Renaissance du livre, 2001, vol. 1, 313.

- Jump up ↑ VANPAEMEL, Geert, "De darwinistische revolutie", in Robert Halleux, Geert Vanpaemel, Jan Vandersmissen en Andrée Despy-Meyer (red.), Geschiedenis van de wetenschappen in België 1815-2000, Brussel: Dexia/La Renaissance du livre, 2001, vol. 1, 266.

- Jump up ↑ "Notes javanaises: protection des fôrets", in: Revue de l'Université de Bruxelles, 1 (1895-1896), 257-263.

- Jump up ↑ For a discussion of this mixture of aesthetic, historical-archival and scientific motives among scientific nature activists, see Raf de Bont and Rajesh Heynickx, "Landscapes of nostalgia”, 247-253.