|

The fact that uranium from Congolese soil ended up in the US atomic bomb via Belgian hands and accordingly changed the Second World War’s course is no longer a secret. Less well known is the important role which the Belgians played in the use of radium for medical applications, such as the treatment of cancer. Between 1923 and 1933, Belgium even dominated the global radium market, thanks to a steady import from its colony, the Congo. The fact that a small country like Belgium became a world player in the radio industry is all the more surprising because the discovery and first experiments with radium were reserved for foreigners.

The discovery and first applications of radium: trial and error

|

|

| Henri Bequerel Source: Basdevant, Jean-Louis, ‘L’enseignement d’Henri Bequerel à L’Ecole Polytechnique (1895-1908)’, in: Bulletin de La Société Des Amis de La Bibliothèque et de l’histoire de l’Ecole Polytechique <https://journals.openedition.org/sabix/546?lang=en#quotation>, page consulted on 29 January 2020.

|

Radioactive substances and radiation, like so many scientific phenomena, were discovered coincidentally and accidentally. The French physicist and engineer Henri Becquerel found out that radium, a substance discovered by Pierre and Marie Curie in 1898, was radioactive.[1] He was burned by a tube of radium which he had forgotten in his jacket pocket. Radium rays were soon seen as an alternative to the X-rays discovered by Wilhelm Röntgen, a German physicist and engineer, in 1895. He had accidentally stuck his hand into a beam of radiation emanating from an electrified tube and saw it appear on a fluorescent screen.[2]

Röntgen’s hand lit up due to the energy which electrons, the negative elements of an atom (the building blocks of substances), release when they collide between the poles of an electrified tube. Becquerel’s skin cells were damaged by the radiation which an unstable atom with too much energy released when it lapsed into a more stable, energy efficient variant. Around the end of the nineteenth century, the scientists in question did not know enough about the structure and working of atoms to fully understand the phenomenon of radioactive radiation. To find out more, they started experimenting, using themselves as test subjects. The injuries which this caused, did not make them shy away, on the contrary. Scientists like Marie Curie soon realised that the discovered rays would change medical imagery and diagnostics and the treatment of all sorts of conditions, such as cancer, for good.

Through trial and error, they developed all kinds of methods, ranging from injecting radium into the skin to irradiating tumours with radium. This time patients served as guinea pigs, in exchange for getting better. During the first years of the twentieth century, scientists and doctors quickly booked results: patients’ tumours reduced and their pain disappeared. Bad side effects, such as nausea and additional tumours, both in patients and doctors, were accepted, because of the positive results and ignorance. All parties involved were driven by the optimism and belief in scientific progress that prevailed at the time. Becquerel and the Curies won Nobel Prizes for their pioneering work. Radium institutes were established in several European cities. These exciting developments did not leave the generally cautious Belgian scientists and doctors indifferent.

Belgium and radium extraction and therapy: a small country with a major impact

A difficult start: foreign inspiration and radium shortages

Around the end of the nineteenth century, Belgian medicine and public cancer health, as well as the scientific disciplines which could contribute to treatment, such as chemistry, were still in their infancy. Cancer was then generally seen as an incurable and sad disease with "festering wounds" and "red-blue glands" which caused enormous suffering.[3] From the beginning of the twentieth century, a new generation of scientists and physicians took scientific research on radioactivity, medical treatment of cancer, and the organisation of health care in Belgium to a higher level. Initially, they looked across national borders. Journals and conferences kept them up to date with foreign insights. They also expanded techniques developed by French, German, and British scientists and doctors, such as curie therapy (holding radium against the skin). Institutions were organised according to foreign examples. In 1891, the Belgian Red Cross, founded by the Swiss Henry Dunant in 1864, was transformed into an institution of public benefit. In 1908, the Board of Public Health established a cancer study commission.

|

|

| Man with radium tubes attached to his tumour Source: Van Helsland, Daphné, (Be)stralende geneeskunde: radio- en radiumtherapie als behandeling van kanker in België van 1895 tot 1945, Unpublished masters thesis, KU Leuven, academic year 2018-2019, p. 65.

.

|

Once the Belgians got their hands on some radium, home-grown innovations and organisations followed. Walter Mund, a chemist who taught at the University of Leuven, was one of the first Belgians to research radium in the famous Parisian Institut de Radium of the Curies. Initially, physicians from different disciplines showed interest in cancer and radium. It was only at the end of his long career, focused on the treatment of war wounds, that Antoine Depage turned his attention to the fight against cancer. Adrien Bayet, attached to the Free University of Brussels (ULB), drew on his experience in venereal diseases when studying cancer. Félix Sluys and Joseph Maisin were the first cancer and radium physicians pur sang, devoting themselves entirely to oncology and radiology. Both had studied abroad in some renowned institutions, such as the Rockefeller Foundation. It was this generation of doctors which advocated seeing cancer as a “social plague”, to be “fought” through scientific and social cooperation, rather than as an incurable individual disease.

These doctors also investigated how radiation therapy could be adapted to the type of cancer and how to combine it with surgery. Despite the progress, the first doubts arose, particularly because radium was so expensive and scarce. The First World War brought scientific and medical activity to a standstill for a while. Because of this conflict, none other than Marie Curie and her daughter Irène, who had followed in her mother's chemical footsteps, toured the Westhoek to equip field hospitals with radiographic equipment. The fact that scientific research and medical developments took off again in Belgium so quickly after the war was mainly due to the Congo, the immense African colony it had owned since 1908.

The radium boom (1922-1932)

From Shinkolobwe to Olen

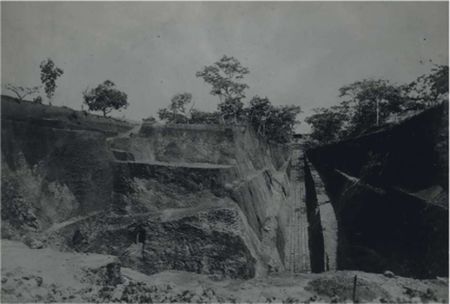

Shinkolobwe, in the heart of Katanga, the most industrialised province of the Belgian Congo, 1915. Robert Rich Sharp, a moustachioed, autodidactic British prospector of Union Minière du Haut-Katanga (UMHK), the largest mining company in the Congo, was looking for copper and adventure. He did not find the first, but the second all the more: he stumbled upon a particularly rich uranium ore, which also contains radium. Unaware of the major consequences of his extraordinary find, he marked it with an ordinary wooden post. UMHK and Société Générale de Belgique (SGB), the powerful financial holding behind the company - and the lion's share of the colonial economy - did not let the First World War stop them from starting with mining uranium and radium as soon as possible. In Shinkolobwe a mining plantation, manned by Congolese workers, was hastily built. In the rural Belgian municipality of Olen (Province of Antwerp) an industrial plant appeared out of the blue. It was part of the Société Générale Métallurgique d'Hoboken, which was also owned by SGM. Here radium and uranium were isolated, packaged, and sent to buyers.

There was barely a year between the arrival of the first 12 tonnes of uranium from the Congo in 1921 and the production of the first gram of “Belgian radium” in 1922. Because American competitors soon gave up, UMHK was able to dominate the global uranium market with the help of the Belgian government. In the mid-1920s, the company supplied 80 per cent of the world's radium. What's more, the Katangese mining giant even had the exclusive substance on surplus. To mislead its competitors, it kept silent about the production and sale of radium.

Soon enough, the company was accused of deliberately keeping radium prices too high, in particular by the British. They argued that the company was only concerned with making a profit, at the expense of dying sick people who could not afford the extremely expensive radium treatments. Various British doctors even committed suicide in protest. In vain, the British government knocked on the door of the League of Nations to bypass UMHK. Initially, the company kept a stiff upper lip. During the 1930's prices slowly dropped, simply because UMHK produced and sold a lot of radium. In 1933, one gram of radium cost 'only' $55,000.[4]

From Leuven to Spa

UMHK and SGB realised that they had to commercialise and democratise radium if they really wanted to make a profit. The company, again encouraged by the Belgian government, set up a commercial department. It promoted radium as the latest medical miracle cure, which was not the privilege of a few rich people. The most remarkable and impactful stunt - initially the idea of Louis Franck, the Minister of Colonies - was the sale of radium to the University Foundation, which in turn lent the substance to university research centres and hospitals. These were then able to offer relatively cheap treatments by means of government subsidies. This marked the start of the short but powerful “Golden Age” of radium therapy in Belgium.

Of the four universities that could count on the government and UMHK for a regular supply of radium, the one in Leuven was the most successful. The University of Leuven had attracted some of the best experts, such as Maisin. Rector Monsignor Paulin Ladeuze insisted that this bright young man had to receive the new chair of “anatomical pathology, radiology, and cancerology”. Two years later, Maisin was promoted to professor and founded the Institut d’Anatomie Pathologique. This institute, known as the “Cancer Institute”, was partly built with public donations collected in the name of the “honour of Catholic science”.[5] The institute had tele-curie and X-ray equipment, a radiological and surgical service, a team of doctors and nurses - les demoiselles de la télé - and a radio bomb.[6] This was a device used to irradiate patients with a large amount of radium in an especially designed underground bunker. Foreign researchers were very impressed by the expertise, the organisation, and the results of the optimistic and proud “little Belgians”.

Other Belgian cities were also buzzing with medical activity. Depage was chairman of the Belgian Red Cross, within which a Radium Institute in Berkendael, headed by Sluys, was established. Both doctors treated patients in their hospitals in Brussels. In 1924, Depage and Bayet jointly founded the Belgian National League for Cancer.

The reputable Belgian doctors often attracted famous patients from all over the world. In November 1924 none other than Giacomo Puccini, the opera composer known for Madama Butterfly, knocked on the door of Sluys' hospital on the Place de Trône (nowadays the Raymond Blyckaerts Square) in Ixelles. For years, the Italian had suffered from a severe sore throat and continuous coughing fits, caused by a throat tumour, which was the result of a smoke addiction. Italian doctors had referred Puccini to Sluys, instead of Berlin doctors, not only because of his expertise. Sluys was also chosen because he spoke Italian, had extensive connections as a music lover and pivotal figure in the Brussels cultural scene, and the good relations between Italy and Belgium. A climate of intellectual cooperation was thus a crucial element which facilitated the exchange of scientific expertise. Puccini loved Brussels and was convinced that his love affair with the city would continue after a quick and successful operation. Everything was done to dote the composer with a treatment that suited his status. He received champagne through a nose tube, something that was not done for every cancer sufferer. To no avail. After an operation that lasted more than three hours Puccini was in a lot of pain and fainted. A heart attack caused by persistent heavy bleeding eventually killed him. Sluys had never told the Italian how bad his condition was and that there was little hope for a cure. Statements of support came from all corners, including the Belgian royal family. Belgian and foreign newspapers reported extensively on Puccini's funeral service. These were very public reminders that the Belgians could not perform miracles.

|

|

| News coverage of Puccini's death Source: Giacomo Puccini: Mori Con Liu, Brussel, Lucchesi nel Mondo, 1994.

.

|

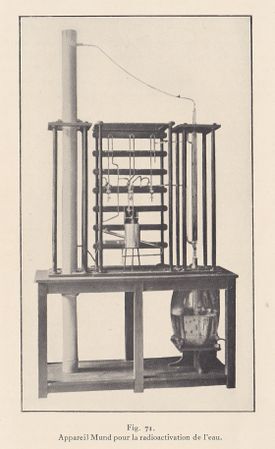

Belgians also stood at the cradle of new techniques. Mund brought a device that produced radioactive water on the market. Sick people could drink this water, bathe in it and, mixed with mud, spread it on themselves at the Centre d’Emanotherapie in Spa. Home delivered bottles with a personalised dose were also available. The line between proper medical treatments and quackery was very thin. People without expertise but with a nose for business sold radium mixed with vaseline and in powder form. Such goods were touted as a panacea for a whole host of diseases and as the secret to eternal beauty. Doubts about the adverse effects of radium and the minimum protection for those who came into direct contact with it were suppressed at own risk. The horror story of the man who eagerly drank more than 1000 bottles of radium water until his jaw fell off and eventually even died was only one of many that circulated.

Radium bust: 1932-1945

At the beginning of the 1930s, attempts were made to centralise the various cancer services in Belgium and to stimulate interdisciplinary cooperation, to obtain improved treatment and cheaper radium. Mutual incomprehension and distrust prevented better cooperation between doctors, surgeons, and chemists. Greater coordination between university departments and national institutions was prevented by tensions between Dutch and French speakers and Catholics and liberals. Sometimes personal issues also played a role. A plan for a merger between the Cancer League and the Radium Institute of the Red Cross was exchanged for one of merely better cooperation after Depage's sudden death in 1925. Several individuals, such as Maisin and Professor Zénon Marcel Bacq, who was associated with the ULB and the University of Liège, joined forces, resulting in the flourishment of oncological, radiological and immunological research. Despite these individual successes, the institutional delays and conflicts, which often dragged on into the 1960s, caused frustration among Belgian doctors. Maisin warned the Rector of the University of Leuven, Albert Descamps, that the problems would cost the Leuven institution its pole position.[7]

|

|

| Mund's machine Bron: Mund, Walter, Les Bases Physico-chimiques de l’Emanothérapie, Spa, Compagnie fermière des eaux et bains, 1928.

|

The first real dark clouds appeared over Shinkolobwe and Olen when UMHK lost its “glorious pre-war monopoly” on radium.[8] Despite having well digested the Great Depression of the 1930's, the company found it increasingly difficult to hold off new Canadian competitors. Initially, the Belgians relied on their head start. They were also increasingly present on the international stage and stimulated cooperation and information exchange across national borders. Belgium joined the Union for International Cancer Control, an intergovernmental organisation that promoted international cooperation in cancer research, treatment, and prevention. Maisin became its Secretary-General (1935) and President (1953-1958).

During the Second World War, the Leuven Cancer Institute was occupied by the Germans and the equipment was partly damaged by bombing. The Germans even confiscated the radium, which led to the institute’s shut down for five months. When the Germans returned the radium after long negotiations, UMHK decided to add a few grams. In 1943, Maisin proudly spoke of a world first: the Leuven Cancer Institute owned the largest radium bomb in the world.[9] It was immediately one of the last highlights of the Belgian radium industry.

Although radium therapy was still applied in the 1940s and 1950s, pessimism about the high cost of radium and its harmful effects increasingly prevailed. Experiments and treatments with it were gradually exchanged for newer versions with cobalt and X-rays and chemotherapy. The fact that radioactive substances were increasingly used in nuclear weapons changed attitudes towards radium for good. Towards the end of the Second World War, Belgium and Congo, known worldwide for their radium, were on the eve of a new global nuclear controversy, this time with uranium in the leading role.

The contemporary legacy of radium

On 6 August 1945, the Americans dropped the atomic bomb "Little Boy", manufactured with uranium mined from Congolese soil, on the Japanese city of Hiroshima. Not only did this put an immediate end to the Second World War, it also marked a turning point in the Belgian and global nuclear story. In the aftermath, ever more voices around the globe were raised in favour of peaceful nuclear applications. Belgians, such as Pierre Ryckmans, former Vice-Governor General of the Belgian Congo, also played a key role this time. The Atomium in Brussels, built for the Expo '58 World Fair, symbolised how they were once again tempted into being optimistic about nuclear matters. Shinkolobwe again played an important role by supplying the uranium for Belgium's first nuclear power station. Despite being at the basis of the new nuclear energy chapter, the mine was gradually running out minerals. It was only finally closed in 2004. The Olen plant got even less time: it was closed in 1975 and demolished in the 1980s.

Today, radium has not completely disappeared. At the Aquacentrum Agricola in Jachymov, the contemporary Czech version of the radium centre in Spa, you can still dive into a radium bath to reduce your pain or increase your sexual energy. The radioactive waste mountains in Olen and Shinkolobwe are silent warnings of the substance’s harmful properties. Radioactive substances are also slowly gaining a place in our collective memory and continue to appeal to the imagination. Sharp himself set the mythologisation of radium in motion by portraying himself as a hero, who changed history in his memoirs. Well-known Belgian doctors, such as Bayet, now live on in street and hospital names.

The film Radium Girls (2018), directed by Lydia Dean Pilcher and Ginny Mohler, portrays the women who contracted radium poisoning by painting clock hands with luminous paint. In the novel The Laughing Monsters (2014), written by Denis Johnson, a special role is reserved for a lump of uranium from the Shinkolobwe mine. Such media forms show how imagination and reality, optimism and danger converged in the story of radium, Belgium's best known export product between 1923 and 1933.[10] Popular works telling the tale of the Belgians’ pivotal role in the radium boom and bust and its transformation from one of the most exclusive substances to something that ordinary citizens powdered on themselves against all sorts of ailments - for better or worse - have yet to be made.

Literature

Adams, Anne, ‘The Origins and Early Development of the Belgian Radium Industry’, in: Environment International, 19 (1993), 491–501.

Balduck, Paul, ‘Marie en Irène Curie aan het IJzerfront’, Mens & Molecule <https://www.mensenmolecule.be/verenigingen/marie-en-irene-curie-aan-het-ijzerfront>, page consulted on 29 Januari 2020.

Barbé, Luc, België En de Bom. De Rol van België in de Proliferatie van Kernwapens <http://www.lucbarbe.be/sites/default/files/boek/files/Belgie-en-de-bom.pdf>, PDF consulted on 29 Januari 2020.

Basdevant, Jean-Louis, ‘L’enseignement d’Henri Bequerel à L’Ecole Polytechnique (1895-1908)’, in: Bulletin de La Société Des Amis de La Bibliothèque et de l’histoire de l’Ecole Polytechique <https://journals.openedition.org/sabix/546?lang=en#quotation>, page consulted on 29 Januari 2020.

Cottyn, Hans, ‘De Belg, de Brit En de Bom’, De Standaard, 11 April 2015.

Franciosi, Maria Laura, ‘The day when Giacomo Puccini died in Brussels’, Brussels Express, <https://brussels-express.eu/day-giacomo-puccini-died-brussels/>, page consulted on 29 Januari 2020.

Giacomo Puccini: Mori Con Liu, Brussel, Lucchesi nel Mondo, 1994.

Hens, Tine, ‘Stralen in Het Radium Palace’, MO*magazine, 2019 <https://www.mo.be/column/stralen-het-radium-palace>, page consulted on 29 Januari 2020.

‘La Chute d’Anvers et La Question de La Presse Vues Par Adrien Bayet’, Archives et Musée de La Littérature <http://1418.aml-cfwb.be/chronologie/1914/10/bayet>, page consulted on 29 Januari 2020.

Mund, Walter, Les Bases Physico-chimiques de l’Emanothérapie, Spa, Compagnie fermière des eaux et bains, 1928.

‘Radium Girls’, IMDb <https://www.imdb.com/title/tt6317180/>, page consulted on 29 January 2020.

‘Radium, made in Belgium’, EOS Wetenschap, <https://www.eoswetenschap.eu/natuurwetenschappen/radium-made-belgium>, page consulted on 29 Januari 2020.

Van Helsland, Daphné, (Be)stralende geneeskunde: radio- en radiumtherapie als behandeling van kanker in België van 1895 tot 1945, Unpublished masters thesis, KU Leuven, academic year 2018-2019.

Van Tiggelen, René, Eerste Wereldoorlog in België: Radiologie in Trench Coat, The Hague, Boom, 2011.

Vandendriessche, Joris, ‘De grootste bom ter wereld’, Cultuurgeschiedenis.be <http://cultuurgeschiedenis.be/de-grootste-bom-ter-wereld/>, page consulted on 29 Januari 2020.

Vandendriessche, Joris, Zorg en Wetenschap: een Geschiedenis van de Leuvense Academische Ziekenhuizen in de Twintigste Eeuw, Leuven, Universitaire Pers Leuven, 2019.

Vanpaemel, Geert, ‘De Natuurkunde’, in: Geschiedenis van de Wetenschappen in België. 1815-2000, ed. by Despy-Meyer, André, Halleux, Robert, Vandersmissen, Jan, Vampaemel, Geert, Brussels, Dexia Bank, 2001, 125-142.

References

- ↑ The chemical element radium has atomic number 88 in the Periodic System and is abbreviated as Ra.

- ↑ Röntgen also captured the first radiographic image of his wife's hand.

- ↑ Vandendriessche, Joris, Zorg en Wetenschap: een Geschiedenis van de Leuvense Academische Ziekenhuizen in de Twintigste Eeuw, Leuven, Universitaire Pers Leuven, 2019, p. 61.

- ↑ Adams, Anne, ‘The Origins and Early Development of the Belgian Radium Industry’, in: Environment International, 19 (1993), 499.

- ↑ Vandendriessche, Joris, Zorg en Wetenschap: een Geschiedenis van de Leuvense Academische Ziekenhuizen in de Twintigste Eeuw, Leuven, Universitaire Pers Leuven, 2019, p. 62. en Van Helsland, Daphné, (Be)stralende geneeskunde: radio- en radiumtherapie als behandeling van kanker in België van 1895 tot 1945, Onuitgegeven masterthesis, KU Leuven, academiejaar 2018-2019, p. 36.

- ↑ Vandendriessche, Joris, Zorg en Wetenschap: een Geschiedenis van de Leuvense Academische Ziekenhuizen in de Twintigste Eeuw, Leuven, Universitaire Pers Leuven, 2019, p. 86.

- ↑ Vandendriessche, Joris, Zorg en Wetenschap: een Geschiedenis van de Leuvense Academische Ziekenhuizen in de Twintigste Eeuw, Leuven, Universitaire Pers Leuven, 2019, p. 62.

- ↑ Adams, Anne, ‘The Origins and Early Development of the Belgian Radium Industry’, in: Environment International, 19 (1993), 499.

- ↑ Vandendriessche, Joris, ‘De grootste bom ter wereld’, Cultuurgeschiedenis.be, <http://cultuurgeschiedenis.be/de-grootste-bom-ter-wereld/>, page consulted on 29 January 2020

- ↑ Adams, Anne, ‘The Origins and Early Development of the Belgian Radium Industry’, in: Environment International, 19 (1993), 499.

|