Difference between revisions of "Colonial High School"

m |

|||

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

The Higher Colonial School (École Coloniale Supérieure) was a training institute for future colonials. It was founded in 1920 in Antwerp and renamed the Colonial High School of Belgium (Université Coloniale de Belgique) in 1923. From 1949 onwards, it was renamed University Institute for the Overseas Territories (UNIVOG) (Institut Universitaire des Territoires d'Outre-mer (INUTOM)). After the school was discontinued in 1961, it underwent several mergers, eventually producing the Institute of Development Policy and Management (IOB) of the University of Antwerp. The original building is located on Campus Middelheim. | The Higher Colonial School (École Coloniale Supérieure) was a training institute for future colonials. It was founded in 1920 in Antwerp and renamed the Colonial High School of Belgium (Université Coloniale de Belgique) in 1923. From 1949 onwards, it was renamed University Institute for the Overseas Territories (UNIVOG) (Institut Universitaire des Territoires d'Outre-mer (INUTOM)). After the school was discontinued in 1961, it underwent several mergers, eventually producing the Institute of Development Policy and Management (IOB) of the University of Antwerp. The original building is located on Campus Middelheim. | ||

| − | :<font color="2F4F4F"> | + | :<font color="2F4F4F">| ''Story about the discussion on colonial sciences, administration, and the elite at the Colonial High School, see https://www.bestor.be/wiki_nl/index.php/The_Colonial_High_School:_an_arena_for_discussions_on_the_colonial_sciences,_administration,_and_elite''.</font> |

| Line 17: | Line 17: | ||

<br>In response to increasing complaints about the colonial administrators during the First World War, policymakers agreed that a new school and training were needed. In 1919, Minister of Colonies Louis Franck set up a preparatory committee, which considered the admission, duration, and content of a training course for colonials. Already a year later, the Higher Colonial School (École Coloniale Supérieure) was established in Antwerp by the Royal Decree of 11 February 1920. Charles Lemaire, a military and explorer who had spent most of his career in Congo, was appointed as the first director. He also taught cartography and deontology. In 1921, a student club, with orange, white and blue as official colours, was established. | <br>In response to increasing complaints about the colonial administrators during the First World War, policymakers agreed that a new school and training were needed. In 1919, Minister of Colonies Louis Franck set up a preparatory committee, which considered the admission, duration, and content of a training course for colonials. Already a year later, the Higher Colonial School (École Coloniale Supérieure) was established in Antwerp by the Royal Decree of 11 February 1920. Charles Lemaire, a military and explorer who had spent most of his career in Congo, was appointed as the first director. He also taught cartography and deontology. In 1921, a student club, with orange, white and blue as official colours, was established. | ||

| − | <br>Funding came from the Belgian state, the city of Antwerp (which also donated a plot of land near the Middelheim Park), the Association des Planteurs de Caoutchouc, the Casteleyn Fund, the Fondation des Amis de l'Université Coloniale (initiative of Paul Gustin), Edouard Bunge's Bunge Foundation, and the Commission for Relief in Belgium, a predominantly American foundation that organised food supplies in Belgium during the First World War.<ref>The Bunge family had been involved in the import and export of colonial goods since the Congo Free State period.</ref> | + | <br>Funding came from the Belgian state, the city of Antwerp (which also donated a plot of land near the Middelheim Park), the ''Association des Planteurs de Caoutchouc'', the Casteleyn Fund, the ''Fondation des Amis de l'Université Coloniale'' (initiative of Paul Gustin), Edouard Bunge's Bunge Foundation, and the Commission for Relief in Belgium, a predominantly American foundation that organised food supplies in Belgium during the First World War.<ref>The Bunge family had been involved in the import and export of colonial goods since the Congo Free State period.</ref> |

| Line 27: | Line 27: | ||

|[[Image: Koloniale Hogeschool 01.jpeg|450x450px|none]] | |[[Image: Koloniale Hogeschool 01.jpeg|450x450px|none]] | ||

|-align="left" valign="top"" | |-align="left" valign="top"" | ||

| − | |width="100"|'''De Koloniale Hogeschool''' <small>Source: Vanhees, B., ‘Een opmerkelijke carrière. | + | |width="100"|'''De Koloniale Hogeschool''' <small>Source: Vanhees, B., ‘Een opmerkelijke carrière. Norbet Laude en de Koloniale Hogeschool van Antwerpen’, ''Retroscoop'' http://www.retroscoop.com/maatschappij.php?artikel=172, consulted 17 March 2020.</small> |

|} | |} | ||

| − | <br>In the long run, little of the plans for expansion and collaboration was realised. In the end, only the Faculty of State and Administrative Sciences became a fully-fledged faculty. When the School of Tropical Medicine moved to Antwerp, it chose a new building instead of the campus of Colonial High School. Moreover, despite the name change, the school was unable to deliver university degrees. The changes thus | + | <br>In the long run, little of the plans for expansion and collaboration was realised. In the end, only the Faculty of State and Administrative Sciences became a fully-fledged faculty. When the School of Tropical Medicine moved from Brussels to Antwerp, it chose a new building instead of the campus of Colonial High School. Moreover, despite the name change, the school was unable to deliver university degrees. The changes were thus merely an internal reorganisation, rather than a real restructuring. |

<br>After Lemaire relinquished the directorship due to illness, a new director was appointed in 1926: Norbert Laude. He was a soldier who, after surviving the First World War in the Congo, worked for the propaganda service of the Ministry of Colonies. Aiming to increase student discipline, he introduced a boarding school regime and uniform. He also gave the programme its final form and, like Lemaire, taught himself. Finally, he promoted the school in the media and through lectures and networked in Belgium and abroad. | <br>After Lemaire relinquished the directorship due to illness, a new director was appointed in 1926: Norbert Laude. He was a soldier who, after surviving the First World War in the Congo, worked for the propaganda service of the Ministry of Colonies. Aiming to increase student discipline, he introduced a boarding school regime and uniform. He also gave the programme its final form and, like Lemaire, taught himself. Finally, he promoted the school in the media and through lectures and networked in Belgium and abroad. | ||

| − | <br>In 1929, the school had to deal with a problem of a completely different order: a fire in the main building destroyed a large part of the classrooms and collections. The library, including the bust of Lemaire, survived the fire unharmed. Rumour had it that, following this hard blow, the school would close down or, at best, merge with other institutions . But Laude would not hear of it. He did everything to ensure that 'his school' was rebuilt. With result: the new building was festively opened | + | <br>In 1929, the school had to deal with a problem of a completely different order: a fire in the main building destroyed a large part of the classrooms and collections. The library, including the bust of Lemaire, survived the fire unharmed. Rumour had it that, following this hard blow, the school would close down or, at best, merge with other institutions. But Laude would not hear of it. He did everything to ensure that 'his school' was rebuilt. With result: the new building was festively opened in 1931. |

| Line 46: | Line 46: | ||

|[[Image: Laude_na_de_Tweede_Wereld_Oorlog.jpeg|450x450px|none]] | |[[Image: Laude_na_de_Tweede_Wereld_Oorlog.jpeg|450x450px|none]] | ||

|-align="left" valign="top"" | |-align="left" valign="top"" | ||

| − | |width="100"|'''Laude | + | |width="100"|'''Laude after the Second World War''' <small>Source: Vanhees, B., ‘Een opmerkelijke carrière. Norbet Laude en de Koloniale Hogeschool van Antwerpen’, ''Retroscoop'' http://www.retroscoop.com/maatschappij.php?artikel=172, consulted 17 March 2020.</small> |

|} | |} | ||

| Line 68: | Line 68: | ||

:<font color="2F4F4F">| ''For a complete list with lecturers, see Vanhees, B., ‘Een opmerkelijke carrière. Norbet Laude en de Koloniale Hogeschool van Antwerpen’, ''Retroscoop'' http://www.retroscoop.com/maatschappij.php?artikel=172, consulted 17 maart 2020''.</font> | :<font color="2F4F4F">| ''For a complete list with lecturers, see Vanhees, B., ‘Een opmerkelijke carrière. Norbet Laude en de Koloniale Hogeschool van Antwerpen’, ''Retroscoop'' http://www.retroscoop.com/maatschappij.php?artikel=172, consulted 17 maart 2020''.</font> | ||

| − | <br>The lecturers were often former colonials and missionaries who were also active in other institutions with a colonial connection, such as the Museum of Tervuren and the Ministry of Colonies, Belgian universities and colleges. Initially a course lasted | + | <br>The lecturers were often former colonials and missionaries who were also active in other institutions with a colonial connection, such as the Museum of Tervuren and the Ministry of Colonies, Belgian universities and colleges. Initially a course lasted three years. In the long term, it was extended to four years. Successfully completing the first two-year cycle resulted in a kandidaatsdiploma [bachelors degree] in colonial and administrative sciences. Students who finished the last two years received a 'licentiaatsdiploma' [masters degree] in the colonial and administrative sciences. |

| Line 97: | Line 97: | ||

|[[Image: Gasten_bij_de_inhuldiging_van_het_monument.jpeg|450x450px|none]] | |[[Image: Gasten_bij_de_inhuldiging_van_het_monument.jpeg|450x450px|none]] | ||

|-align="left" valign="top"" | |-align="left" valign="top"" | ||

| − | |width="100"|''' | + | |width="100"|'''Guests at the inauguration of the monument''' <small>Source: Vanhees, B., ‘Een opmerkelijke carrière. Norbet Laude en de Koloniale Hogeschool van Antwerpen’, ''Retroscoop'' http://www.retroscoop.com/maatschappij.php?artikel=172, consulted 17 March 2020.</small> |

|} | |} | ||

| Line 130: | Line 130: | ||

Vanhees, B., ‘Een opmerkelijke carrière. Norbet Laude en de Koloniale Hogeschool van Antwerpen’, 'Retroscoop' [http://www.retroscoop.com/maatschappij.php?artikel=172, consulted 17 March 2020]. | Vanhees, B., ‘Een opmerkelijke carrière. Norbet Laude en de Koloniale Hogeschool van Antwerpen’, 'Retroscoop' [http://www.retroscoop.com/maatschappij.php?artikel=172, consulted 17 March 2020]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Notes=== | ||

| + | <references/> | ||

Latest revision as of 14:23, 6 April 2020

The Higher Colonial School (École Coloniale Supérieure) was a training institute for future colonials. It was founded in 1920 in Antwerp and renamed the Colonial High School of Belgium (Université Coloniale de Belgique) in 1923. From 1949 onwards, it was renamed University Institute for the Overseas Territories (UNIVOG) (Institut Universitaire des Territoires d'Outre-mer (INUTOM)). After the school was discontinued in 1961, it underwent several mergers, eventually producing the Institute of Development Policy and Management (IOB) of the University of Antwerp. The original building is located on Campus Middelheim.

- | Story about the discussion on colonial sciences, administration, and the elite at the Colonial High School, see https://www.bestor.be/wiki_nl/index.php/The_Colonial_High_School:_an_arena_for_discussions_on_the_colonial_sciences,_administration,_and_elite.

Contents

[hide]History

Establishment

The Colonial College of Belgium was not the first institution in Belgium to train colonials before they left for the Congo. As early as 1894, King Leopold II, the private owner of the Congo Free State (1885-1908), set up the Ecole Mondiale in Tervuren. It, however, never got off the ground. After Belgium took over Léopold's colony and renamed it the Belgian Congo, it also re-established the monarch's colonial school. It offered only limited training and attracted few students.

In response to increasing complaints about the colonial administrators during the First World War, policymakers agreed that a new school and training were needed. In 1919, Minister of Colonies Louis Franck set up a preparatory committee, which considered the admission, duration, and content of a training course for colonials. Already a year later, the Higher Colonial School (École Coloniale Supérieure) was established in Antwerp by the Royal Decree of 11 February 1920. Charles Lemaire, a military and explorer who had spent most of his career in Congo, was appointed as the first director. He also taught cartography and deontology. In 1921, a student club, with orange, white and blue as official colours, was established.

Funding came from the Belgian state, the city of Antwerp (which also donated a plot of land near the Middelheim Park), the Association des Planteurs de Caoutchouc, the Casteleyn Fund, the Fondation des Amis de l'Université Coloniale (initiative of Paul Gustin), Edouard Bunge's Bunge Foundation, and the Commission for Relief in Belgium, a predominantly American foundation that organised food supplies in Belgium during the First World War.[1]

Restructuring and Fire

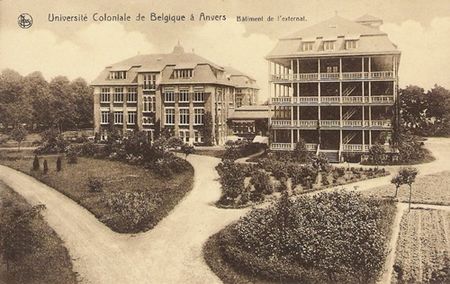

The Colonial School had many teething problems, such as a shortage of teaching staff. As the problems persisted, the its usefulness was even questioned. To suppress these doubts, the school was renamed, rebuilt, and restructured in 1923. From then on, it was called the Colonial High School of Belgium (Université Coloniale de Belgique). An institute with three faculties, which would each be linked to an existing institution, was created. The Faculty of State and Administrative Sciences was formed by the Colonial High School. The Faculty of Tropical Medicine and the Faculty of Natural Sciences were connected to the School of Tropical Medicine and the Museum of Tervuren respectively. The brand-new buildings, located near the Middelheim Park, were inaugurated by none other than King Albert I. In 1925, a commercial department, financed by the Bunge Foundation, was added. This department focused on those who were interested in doing business in the Congo.

| De Koloniale Hogeschool Source: Vanhees, B., ‘Een opmerkelijke carrière. Norbet Laude en de Koloniale Hogeschool van Antwerpen’, Retroscoop http://www.retroscoop.com/maatschappij.php?artikel=172, consulted 17 March 2020. |

In the long run, little of the plans for expansion and collaboration was realised. In the end, only the Faculty of State and Administrative Sciences became a fully-fledged faculty. When the School of Tropical Medicine moved from Brussels to Antwerp, it chose a new building instead of the campus of Colonial High School. Moreover, despite the name change, the school was unable to deliver university degrees. The changes were thus merely an internal reorganisation, rather than a real restructuring.

After Lemaire relinquished the directorship due to illness, a new director was appointed in 1926: Norbert Laude. He was a soldier who, after surviving the First World War in the Congo, worked for the propaganda service of the Ministry of Colonies. Aiming to increase student discipline, he introduced a boarding school regime and uniform. He also gave the programme its final form and, like Lemaire, taught himself. Finally, he promoted the school in the media and through lectures and networked in Belgium and abroad.

In 1929, the school had to deal with a problem of a completely different order: a fire in the main building destroyed a large part of the classrooms and collections. The library, including the bust of Lemaire, survived the fire unharmed. Rumour had it that, following this hard blow, the school would close down or, at best, merge with other institutions. But Laude would not hear of it. He did everything to ensure that 'his school' was rebuilt. With result: the new building was festively opened in 1931.

Second World War and end

The Second World War was a turbulent period for the Colonial High School. The buildings were temporarily used by the Belgian army and the Red Cross. After Belgium surrendered to the Germans in 1941 and became occupied territory, the school was taken over by German soldiers. They and V-missiles caused a lot of damage to the school. Eventually, a sort of compromise was reached between the school and the Germans: the lessons could continue if the students did some work for the Germans. Laude soon withdrew from the arrangement out of fear that students would fall prey to German propaganda that built upon Flemish-nationalist sentiments. His concerns were not ungrounded, as quite a few students did have connections with Flemish-nationalist associations with a German connection, such as Verdinaso, the 'Verbond der Dieste Nationaal Solidaristen'. In the end it was decided to continue the lessons in mansions on the Elizabethlaan in Antwerp until the end of the war.

The Colonial High School and Laude also played a role in wartime resistance. The director became deputy commander of the Antwerp branch of 'Het Geheim Leger' [The Secret Army], a resistance group, and chairman of the 'Clandestien Coördinatiecomité' [Clandestine Coordination Committee] of Antwerp. An intelligence cell was set up at the school and was supported by students, former students, and teachers. In addition to collecting and disseminating intelligence, KH L55 was also involved in espionage, resistance press, and organising help for people in hiding and resistance actions. In August 1944 the cell was betrayed to the Germans. Laude was arrested, interrogated, tortured and even sentenced to death three times. His execution was narrowly avoided because the Germans had to flee from the British who came to liberate Antwerp. After the war, Laude was widely acknowledged for his role in the resistance.

| Laude after the Second World War Source: Vanhees, B., ‘Een opmerkelijke carrière. Norbet Laude en de Koloniale Hogeschool van Antwerpen’, Retroscoop http://www.retroscoop.com/maatschappij.php?artikel=172, consulted 17 March 2020. |

After the tumultuous war period, the school focused on education again and embarked on a period of success. In 1949 it got another new name: Universitair Instituut voor de Overseas Gebieden (UNIVOG) (Institut Universitaire des Territoires d'Outre-mer (INUTOM)) [The University Institute for Overseas territories]. This time the name change was accompanied by an upgrade to university level. From then on, the institution could issue diplomas of 'candidate' (bachelor) and 'licenciate' (master) in the colonial and administrative sciences. In 1956, a number of Congolese evolués, members of the Europeanised Congolese elite, including Patrice Lumumba, the first Prime Minister of the independent Congo, visited the institution. However, parallel to the situation in Congo, the heyday of UNIVOG was short-lived. One year after the Congo's independence from Belgium, in 1961, the school was discontinued. The Luxembourgian Georges Schmit, who had only been in charge since 1958, could not doing anything to avoid this.

In 1963 the library was sold and in 1965 the student club came to an end. In 1965 the UNIVOG merged with the Rijkshandelhogeschool [State Trade School] and the Hoger Instituut voor Vertalers en Tolken [Higher Institute for Translators and Interpreters] to form the Rijksuniversiteit Centrum Antwerpen [Antwerp State University Centre, RUCA]. The merger of the institute with the International Cooperation department of the Rijkshandelhogeschool led to the creation of the College voor Ontwikkelingslanden [College for Developing Countries]. In its turn, it merged in 2000 with the Centrum Derde Wereld [Third World Centre, Ufsia] to become the Instituut voor Ontwikkelingsbeleid en -beheer, [Institute for Development Policy and Management IOB], attached to the University of Antwerp.

Selection, classes, and training

Only a limited number of students were allowed to register for the course at the Colonial High School. This 'contigent' was fixed each year by the Minister of Colonies. Moreover, only those who passed a rigorous entrance exam were allowed to start. Between 1920 and 1946 about 1500 students attended the school. Thanks to their diploma, the graduates were assured of a place in the colonial administration and were thus one step ahead of those who had followed a course at another institution or who had not been trained.

The curriculum included a wide range of general disciplines that were considered useful for the management of the colony.

First year: Psychology, Belgian History, Historical Criticism, Mineralogy, Ethnography, Natural Law, Introduction to Law, Constitutional Law, Botany, Human and Animal Biology, Dutch Literature, Bantu Linguistics, English Language, French Language and Geography Belgian Congo.

Second Year: Logic, European Literature, Economy, Administrative, Civil Law of Belgian Congo, Soil Science (irrigation), General Technology, Sociology, French, Bantu Linguistics and Colonial History.

Third and fourth year: Ordinary Law, Colonial Charter, Criminal Code, Criminal Procedures, International Law, Fundamental Rights and Concessions, Social Legislation Belgian Congo, Administrative Institutions, Administrative Accounting, Public Finances Belgian Congo, Administrative Law, Tropical Zoology, Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, Tropical Crops, Parliamentary History, Economic Politics, Topography, Infrastructure, Administrative Organization of a Colonial Post, Transport, Statistics and International Economic Treaties, Comparative Colonial Systems, Comparative Public Law, Lingala, Kiswahili and Tropical Agriculture.

- | For a complete list with lecturers, see Vanhees, B., ‘Een opmerkelijke carrière. Norbet Laude en de Koloniale Hogeschool van Antwerpen’, Retroscoop http://www.retroscoop.com/maatschappij.php?artikel=172, consulted 17 maart 2020.

The lecturers were often former colonials and missionaries who were also active in other institutions with a colonial connection, such as the Museum of Tervuren and the Ministry of Colonies, Belgian universities and colleges. Initially a course lasted three years. In the long term, it was extended to four years. Successfully completing the first two-year cycle resulted in a kandidaatsdiploma [bachelors degree] in colonial and administrative sciences. Students who finished the last two years received a 'licentiaatsdiploma' [masters degree] in the colonial and administrative sciences.

Directors

1920-1926: Charles Lemaire

1926-1958: Norbert Laude

1958-1962: Georges Schmit

Alumni

A number of prominent Belgians attended or taught at the colonial college, including:

De Cleene, Natal: ethnographer, common law teacher

Geeraerts, Jef: writer and critic of the colonial regime

Ryckmans, Pierre: Governor General of the Belgian Congo (1934-1946), taught indigenous law and politics.

Sohier, Antoine: Attorney General of the Court of Appeal in Elizabethville (Katangaprovince, Congo), lecturer in indigenous law

Van Bilzen, Anton Jozef "Jef", lecturer on fundamental rights and concessions and social legislation of Belgian Congo.

| Guests at the inauguration of the monument Source: Vanhees, B., ‘Een opmerkelijke carrière. Norbet Laude en de Koloniale Hogeschool van Antwerpen’, Retroscoop http://www.retroscoop.com/maatschappij.php?artikel=172, consulted 17 March 2020. |

Buildings and monuments

The Colonial High School was designed by architect Walter Van Kuyck (1876-1934). It was built in the 'Colonial Style', which was characterised by many balconies. After the fire in the 1930s, the French mansard roofs were replaced by flat versions and an Art Deco dome was added. A five-pointed star, like on the flag of the Belgian Congo, can be found in several places.

In 1949 a monument was erected in honour of the teachers and students of the school who died during the Second World War. The inauguration ceremony was attended by Pierre Wigny, the then Minister of Colonies, and King Elisabeth, a reference to the strong ties that the Belgian royal family had with the school and the Belgian colony in general.

The original building is currently part of the Middelheim Campus of the University of Antwerp. It currently contains the staff services of the rector, departments of finance, education and research, and meeting rooms. In 2010, the building was granted a protected monument status, which means that the original architecture has to be preserved as well as possible.

Bibliography

Bertrams, K., Universités & entreprises: milieux académiques et industriels en Belgique 1880 – 1970, (Brussels: Le Cri, 2006).

Busschaert, L., ‘Norbert Laude (1888-1974). Leven in teken van de kolonie’, online masterthesis, KU Leuven, 2013-2014 consulted 17 March 2020.

Colman, G., ‘Naar een elite voor de gewestdienst van Belgisch-Kongo en Ruanda-Urundi: de studenten van de Koloniale Hogeschool te Antwerpen (1920-1962)’, unpublished masterthesis, Universiteit van Gent, 1987.

De Vlieger, P-J., ‘Tweeënveertig jaar Koloniale Hogeschool in België. Een historisch onderzoek naar de bestaansreden van een instituut‘, unpublished masterthesis, Universiteit van Gent, 2003.

Foutry, V., ‘Belgisch Kongo tijdens het interbellum: een immigratiebeleid gericht op sociale controle’, Belgisch tijdschrift voor Nieuwste Geschiedenis, 14 (1983), 3-4, 461- 488.

Goeman, L., ‘Topambtenaar in Belgisch-Kongo. Een studie naar beeldvorming bij ambtenaren in gewestdienst, van het niveau van gouverneur-generaal tot hulpgewestbeheerder, in de periode 1958-1960’, Online licenciaatscriptie, Universiteit Gent, 1996-1997 consulted 17 March 2020.

Lagae, ‘‘Het echte belang van de kolonisatie valt samen met wetenschap.’ Over kennisproductie en de rol van wetenschap in de Belgische koloniale context’, Vellut, J-L. (red.), Het geheugen van Congo: de koloniale tijd (Ghent: Snoeck, 2005), 131-138.

Poncelet, M., L’Invention des sciences coloniales belges (Paris: Karthala, 2008).

Vanhees, B., ‘Een opmerkelijke carrière. Norbet Laude en de Koloniale Hogeschool van Antwerpen’, 'Retroscoop' consulted 17 March 2020.

Notes

- Jump up ↑ The Bunge family had been involved in the import and export of colonial goods since the Congo Free State period.

![Jroovers, via [1]](/wiki_nl/images/thumb/8/83/Campus_Middelheim_Building_A.jpg/570px-Campus_Middelheim_Building_A.jpg)