|

On 11 February 1920, the Belgian Colonial High School was established. Politicians and colonials consistently believed that the school would become the centre for colonial sciences and education in Belgium and that a colonial elite would emerge from it. What should this discipline and this elite look like? What their exact role was and who would pay for it all? There was little agreement on this all. As a result, the Colonial High School became a place where the discussion on these important colonial scientific themes regularly erupted. Often these concerned lessons and uniforms, but personal feuds and financial intrigues were also not shunned.

- | Short note on the Colonial High School, see Colonial High School.

Foundation: in search of sponsors for colonial education and sciences

From the beginning, science was an important pillar of the colonial enterprise in Congo. Scientists, including geographers and botanists, were involved in the mapping and exploration of the gigantic area in central Africa. When the Belgian King Léopold II wanted to assert his claim on the Congo, he declared that he not only wanted to combat 'indigenous barbarism' and 'Islamic slavery', but also promised that he would ensure that free trade and science could flourish. The establishment of a school from which a colonial elite would graduate and which would focus on science seemed the logical next step. In 1897 the king set up a school with a name that marked the scope of his colonial ambitions: Ecole Mondiale [World School]. Léopold, however, received no political support for his project, which was often the case with his pet projects. Belgian politicians were not in favour of a colonial project that would upset the fragile Belgian political equilibrium and certainly didn't want to pay an arm and a leg. As a result, Leopold's school died a silent death.

In 1908, Belgium annexed Leopold's colony after numerous violent abuses, especially in the rubber industry, were exposed. A few years later, the Ministry of Colonies breathed new life into the colonial school and the associated dream of a colonial elite. It was, however, unsuccessful once again. It did not offer a full-fledged training, but only a short postgraduate course with a limited number of subjects. It in the first instance attracted soldiers and lower judicial and administrative staff instead of the colonials with a higher function which policymakers had in mind. Many colonials also preferred to follow courses at other institutions, such as the School of Tropical Medicine, which existed in Brussels since 1906. Moreover, they could also a separate courses on colonial subjects to their curriculum while studying at Belgian universities.

During the First World War it rained complaints about the shortcomings of the colonial administration. It was also feared that Belgium's colonial administration paled in comparison to that of other colonial powers. Only when faced with growing criticism, did policymakers confess that a new school and education were high in the agenda. Minister of Colonies Louis Franck (1918-1924), who profiled himself as an advocate of a more efficient and humane colonial policy, put his shoulders underneath the project. He did not hide his ambitions: he hoped that everyone who would go to Congo would have a degree from the new school.

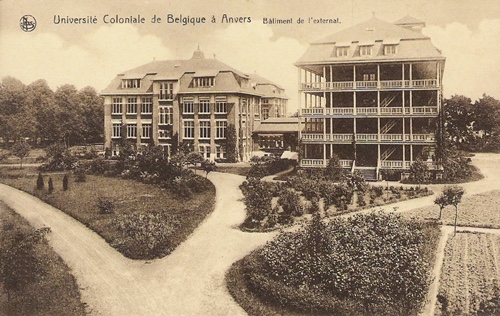

The main stumbling block was a familiar one: where would the money come from? A number of colonial enterprises and associations and the Belgian state made a contribution, as they would all benefit from better trained colonial personnel. Antwerp also provided financial support and donated a building plot in the vicinity of the Middelheim Park. The city believed that the school would be a very prestigious project and hoped to show it off as a benefactor. In the end, political manoeuvring was required to find enough money.

Diplomat and businessman Emile Francqui knew Herbert Hoover, the chairman of the Commission for Relief in Belgium. This was a predominantly American foundation that had organised food supply in Belgium during the First World War. After the conflict, it still had money in surplus. Francqui asked the future President of the United States if 10 million Belgian francs could be used to finance new educational initiatives.

What looked like humanitarian act at first sight, was in fact a handy trick to get funds independently from the Belgian state, which appeared not to be such a generous donor after all. Francqui's actions were not entirely legal either, because he had actually used money intended for the Belgian state without explicit official approval. For unknown reasons, however, the whole thing was never followed up. Once the money was in the bank, everything went very quickly. One year after Minister Franck had set up a preparatory commission, the Colonial High School was established in 1920.

Selection, discipline and vocation: the conditions for a colonial elite

Most of the complaints about the colonial administration were about the shortage of administrators and their poor education. Nevertheless, policymakers in Belgium clung on to the creation a highly educated elite instead of a larger, generally educated group. Belgium had only just confirmed its authority after the Leopoldian episode or its claim to Congo had been questioned during the First World War. The Colonial High School seemed like the ideal formula to increase the Belgian colonial prestige. The prestigious character of the school became immediately apparent from the limited number of pupils that were admitted. Each year, the Minister of Colonies determined the 'continent', based on the number of positions which had to be filled in the colony. He reasoned that only those who could effectively find a job in Congo, should be allowed to start the training.

Moreover, not just anyone was admitted. Candidates had to meet strict selection conditions: they had to have a high school diploma, be able to finance their training themselves, and pass a strict entrance exam. During this exam, candidates had to attend a lecture and write a report about it. They also were also questioned about a specific colonial subject and their general knowledge of Congo. Finally, they had to take a Latin, mathematics or history exam. Candidates had to obtain 65 percent of the points to pass. In exchange for their efforts, they were promised a place in the administration, which meant that they were one step ahead of everyone else who went to Congo.

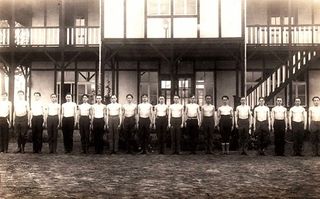

The directors and Franck did not just target clever students. Their ideal student was also disciplined, conscientious, and patriotic and had an exemplary function and a sense of belonging. They were convinced that only such a group could embody a policy based on European civilisation, religion, and science. They therefore emphasised that the colonial administration was not an average profession, but that it had the allure of a vocation. Directors Charles Lemaire and Norbert Laude had acquired such ideas during their time in the army and the colony. That they both had a very similar military-colonial profile, was not a coincidence. The army and military namely played a crucial role in the development of the colony.

After an education at the Royal Military School, Lemaire went to the Congo as part of the first cohort of colonials. His career sounded like a colonial adventure story. He travelled through undiscovered territory, fought battles with Swahili (slave) traders, and undertook various expeditions. Lemaire relinquished his directorship after six years, in 1926, due to illness. His successor, Laude, had survived the First World War in the Congo. After 1921, he continued his colonial career at the Ministry of Colonies, where he became director of the 'Service des Conferences et Informations' [Conference and Information Service]. It is in this function that Laude further developed his idealistic views. Finally, the director was also inspired by scoutism, which at that time was popular all over Europe. He was one of the main instigators of the Belgian Catholic Scouting movement and played a role in establishing a department in the Congo. Such idealistic ideas inspired Laudes' decision to introduce a boarding school regime, student club, and a uniform and to put physical training on the programme.

Scientific and specialised or general and practical knowledge: the content of colonial sciences

Despite the elitist ambitions of policymakers and Laude, the school initially provided middle management staff. Those at the top of the colonial hierarchy - not only in the administration, but also in the judicial and religious domains - usually had a general university degree. Those in the lower ranks most often complemented their secondary or military education with courses from other institutions. Many colonials were fairly confident that they learn most things hands-on in the Congo anyway.

This finding sparked a discussion about what students at the Colonial High School had to learn. Some believed that they should follow a general classical or scientific education, like civil servants in Belgium. Others, however, believed that colonials should acquire specific and practical knowledge because the colony differed so strongly from Belgium on all fronts. This reflected a broader discussion about the nature of the colonial sciences in Belgium and the Congo: should they be of a practical nature, or should they have a more scientific and theoretical character, based on French and British examples?

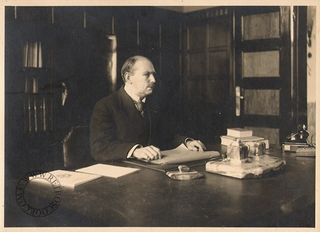

The various directors of the Colonial High School tried to find a compromise. The first one, Lemaire, had collected geological and cartographic data during his time in the Congo. In addition to being a decent scientist, he also turned out to be a good teacher. As a result, he not only headed the school, but also taught cartography and deontology. Lemaire favoured the combination of manual labour and theoretical and scientific knowledge. Laude almost missed out in the position of director due to his lack of scientific credentials. The Colonial High School’s administrative council favoured the other candidate, Major Léopold Borgerhoff, because he had more practical and scientific experience. Laude eventually only got the position because the then Minister of Colonies Henri Carton de Tournai (1924-1926) pushed through the candidacy of his former employee. He emphasised Laude's vision and organisational experience. However, the press was not happy with Laude's appointment and particularly criticised his lack of experience and scientific knowledge.

Laude made every effort to bring together all elements - theory and practical experience, scientific material and general knowledge - in an all-round course. His own directorship reflected this spread. Just like Lemaire, he combined leadership with teaching deontology and geography, which he called 'the mother of the colonial sciences'. He also drew a lot of colonial maps and wrote a handbook Our Colony" [Notre Colonie]. In addition, he also extensively advertised the school through press pieces and by giving lectures and was a networker avant la lettre. Although Lemaire did his utmost to meet everyone's wishes, he received criticism from every corner.

Critics felt he was too authoritarian and believed that only his dependence on the Ministers' approval prevented him from controlling the school and the colonial administrative corps even more than he already did. There were countless conflicts with teachers. Some complained that the subjects focused too much on practical and military experience and criticised their non-academic and unscientific character. They were also upset that Laude taught a subject for which he not been trained. They also felt that the institution was not conducting enough research and condemned the fact that teaching staff mainly consisted of retired servicemen and missionaries instead of qualified teachers. Others found that the school only offered fragmented colonial knowledge instead of a more general education, meaning that the graduates could only work in the Congo or colonial affairs.

Laude's directorship was also seen as a continuation of his previous position, particularly because some of his publications had a strong propagandistic inclination. The name change in 1926 - the school was then called Colonial University of Belgium ('Université Coloniale de Belgique') - and attempts to obtain a university status served to strengthen the school’s scientific character. However, no progress was made in the matter before the Second World War because many felt that the school did not deserve the status as it was simply not scientific enough. Universities were not too keen on an extra competitor.

Other controversies: language, "fetishism" and decolonisation

In addition to discussions about the scientific and elitist nature of the school, it also got involved various other controversies. Not all colonials in the colony welcomed the graduates with open arms. Some administrators, such as Gaston Heenen, Governor of the Katanga Province, and missionaries, such as Jean-Félix de Hemptinne, Apostolic Vicar of Katanga, believed that because the school offered courses on indigenous customs and language it fuelled “coutume fetishism”. They alluded to administrators who they believed had a too positive image of indigenous culture and therefore did not act severely enough against so-called 'primitive customs' or even tolerated them.

The language struggle that dominated Belgian politics and society also shone through in the Colonial High School. Officially, the school offered courses in Dutch and French and both students and teachers had to master both national languages. In practice, however, this was not always the case. Despite efforts to rectify this, language remained a sensitive issue until the very end.

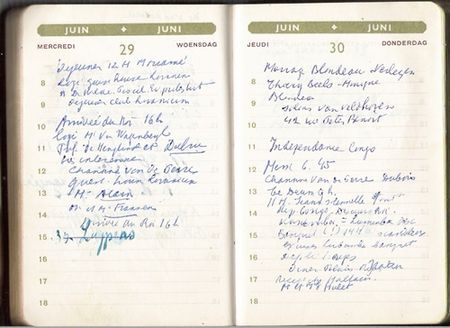

Finally, the school also got caught up in the storm caused by a 1955 proposal about preparing the Congo for independence. The author, Jozef Van Bilsen, was also a lecturer at the school. This, however, did not mean that all of the teachers and students shared his progressive ideas - progressive compared to the majority of colonials who believed that the Congo was far from ready for emancipation - on the contrary. Laude stubbornly stuck to his idealistic and paternalistic vision, which by the 1950s had become quite outdated. Consequently, the Colonial High School did not play a significant role in the decolonisation developments.

Despite initial doubts about his capabilities and the many conflicts during his directorship, Laude was applauded in the long run, mainly for his organisational capabilities. The school also delivered 1500 students in 50 years. These were perhaps not the elite administrators which policy makers targeted or the handy administrators the colonials in Congo were waiting for or the scientists who would make great discoveries, but a mixture of all these elements. This was because the discussion about the nature of colonial sciences, elite, and administration never really came to satisfactory denouement. Despite this, the school was one of the few places where such discussions, and therefore also discussions about the character of the colonial enterprise, effectively took place.

Bibliography

Bertrams, K., Universités & entreprises: milieux académiques et industriels en Belgique 1880 – 1970, (Brussels: Le Cri, 2006).

Busschaert, L., ‘Norbert Laude (1888-1974). Leven in teken van de kolonie’, online masterthesis, KU Leuven, 2013-2014 consulted 17 March 2020.

Colman, G., ‘Naar een elite voor de gewestdienst van Belgisch-Kongo en Ruanda-Urundi: de studenten van de Koloniale Hogeschool te Antwerpen (1920-1962)’, unpublished masterthesis, Universiteit van Gent, 1987.

De Vlieger, P-J., ‘Tweeënveertig jaar Koloniale Hogeschool in België. Een historisch onderzoek naar de bestaansreden van een instituut‘, unpublished masterthesis, Universiteit van Gent, 2003.

Foutry, V., ‘Belgisch Kongo tijdens het interbellum: een immigratiebeleid gericht op sociale controle’, Belgisch tijdschrift voor Nieuwste Geschiedenis, 14 (1983), 3-4, 461- 488.

Goeman, L., ‘Topambtenaar in Belgisch-Kongo. Een studie naar beeldvorming bij ambtenaren in gewestdienst, van het niveau van gouverneur-generaal tot hulpgewestbeheerder, in de periode 1958-1960’, Online licenciaatscriptie, Universiteit Gent, 1996-1997 consulted 17 March 2020.

Lagae, ‘‘Het echte belang van de kolonisatie valt samen met wetenschap.’ Over kennisproductie en de rol van wetenschap in de Belgische koloniale context’, Vellut, J-L. (red.), Het geheugen van Congo: de koloniale tijd (Ghent: Snoeck, 2005), 131-138.

Poncelet, M., L’Invention des sciences coloniales belges (Paris: Karthala, 2008).

Vanhees, B., ‘Een opmerkelijke carrière. Norbet Laude en de Koloniale Hogeschool van Antwerpen’, 'Retroscoop' consulted 17 March 2020.

|