The Masters of science: Belgian Nobel laureates and the pride of the nation

Dining alongside the Queen of Sweden, being the guest of honour at the Scientific Research Fund's jubilee and sipping coffee with King Philippe and Queen Mathilde. These are just some of the privileges granted to Brussels-based professor and physicist François Englert since 10 December 2013, when he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics. But so much honour also means a stifling science minister[1] and a horde of journalists on your tail. "I'm going to hide somewhere", sighed the reluctant physics hero. Englert now joins the illustrious group of Belgian Nobel Prize-winning scientists, whether he likes it or not. Indeed, this was not the first time our proud nation has won, with Jules Bordet, Corneel Heymans, Christian De Duve, Albert Claude and Ilya Prigogine.[2]

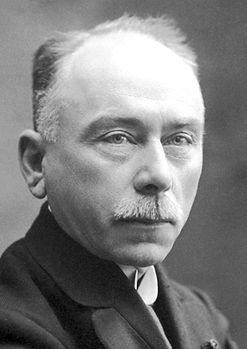

| In 1919, Jules Bordet received the Nobel prize in medicine and physiology. |

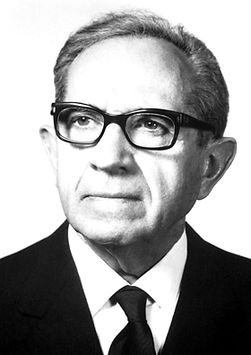

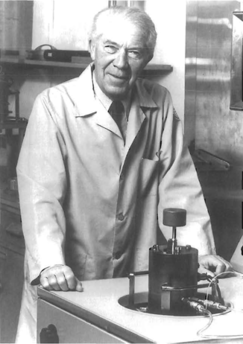

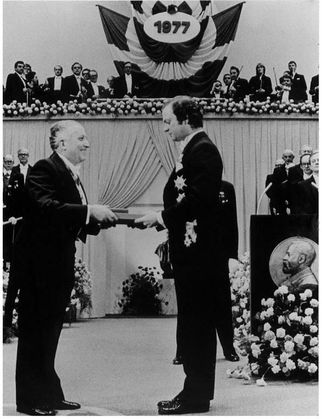

In 1919, the Nobel Prize for Science was awarded for the first time to a Belgian[3], and it was not entirely unexpected that Jules Bordet should win. This bacteriologist from Brussels, associated with the Pasteur Institute, made a good impression with his pioneering work in the field of immunology. The next Belgian winner was Corneel Heymans. This professor from Ghent won the prize in 1938 for his discovery of the importance of carotid corpuscles in the regulation of respiration. In 1974, the Leuven duo of Christian De Duve and Albert Claude (UCL) were the third to win the prize. They won the award for their groundbreaking research into the structure and function of cells. Just three years later, Ilya Prigogine brought a fourth Nobel Prize home to Belgium. The chemist, who was born in Communist Russia but emigrated to Belgium, owes his recognition to his decisive contribution to non-equilibrium thermodynamics, in particular to the theory of dissipative structures.[4]Thanks to Ilya Prigogine, Belgium entered the chemistry department of the Nobel Prizes.

| Corneille Heymans, 1938 Nobel prize in medicine and physiology. |

François Englert, who currently was the latest to join the pantheon of Belgian laureates, was rewarded for his theoretical development of the Brout-Englert-Higgs mechanism, in which a specific particle gives mass to other particles. This tiny particle subsequently became more popular under the name of "Higgs boson", which is easier to pronounce.

Each year, the Nobel Prize rewards a very concrete and specific discovery or piece of research. However, it is more the culmination of a lifetime devoted to science. For the researcher, it is the apotheosis of a long career filled with decorations, titles and honorary doctorates. Most of the prize-winners were no longer novices at the time of their ultimate international recognition. At 46, Corneel Heymans was the exception. As for the others, however, each laureate was greyer than the last. This is a general trend among Nobel Prize winners. Jules Bordet was 49, Christian De Duve 57, Ilya Prigogine 60 and Albert Claude 76! Englert, who won his prize at the age of 81, is the oldest Belgian winner.[5]

The Nobel Prize has always attracted great interest from the general public. All over the world, the annual prize-giving ceremony attracts media attention. Not only do the winners go down in history, but the institutions with which they are associated seize the opportunity to propel themselves into eternal glory. No expense or effort is spared in celebrating the illustrious Nobel gang. The exhausted laureates, just returning from a week of feasting in the far north, are welcomed home with trumpets and much fanfare and are dragged from ceremony to ceremony. Eminent personalities pour cartloads of praise on them. At banquet dinners, each course is being toasted so elaborately that guests are bound to eat the exquisite dishes cold. The champions take rains of applause until their ears tingle and shake hands until their arms are lame. During these parades, they also mostly are presented with gifts; Corneel Heymans, for example, received a gleaming university medal. Jules Bordet, shy and embarrassed, remained impassive when he received a more or less lifelike portrait of himself.

| Albert Claude, Nobel prize in medicine and physiology in 1974. | Christian de Duve, Nobel prize in medicine and physiology in 1974. |

Flowers and medals: the winner is apparently not the only one to boast about it, the institutions are also having a field day. Impatient universities, academies and politicians are trampling over each other in an attempt to make the prizewinner their own. "It is a great honour that has been done to our esteemed colleague", was the message heard at the tribute to Jules Bordet organised by the Academies of Science and Medicine. The director of the Science Class added: "An honour that belongs to the Academy![6] Another professor then stated that Mr Bordet's decoration had definitively established the glory of the Free University of Brussels.[7] And the governor of the province of Brabant, where Mr Bordet headed the Pasteur Institute, exulted not without interest: "The provincial government absolutely wishes to be the first to show its joy and gratitude to the collaborator of whom it is most proud. "Vous êtes son agent cher Maître, que dis-je, vous êtes sa gloire et sa couronne!"[8]

With the same pride, the Université libre de Bruxelles, on the occasion of Englert's award, attributed itself a crucial role as a breeding ground for Nobel winners. On its website, it wrote that "this success is explained by the freedom and the open spirit of research that are part of the university's trademark."[9] And Walloon prime minister Rudy Demotte also builded on the well-known discourse when he noted that Professor Englert's award is an "immense honour for science in Wallonia and Brussels". But however much the institutions try to reclaim the Nobel laureates as one-of-a-kind, they unanimously agree on one thing: the laureates are the 'Maîtres' and 'couronnes' of a glorious Belgian nation.

| Ilya Prigogine receives the Nobel prize in chemistry in 1977. |

For the Nobel laureate, international fame and a life in the spotlight are written in the stars. It is told that during World War II, the German occupiers were so impressed by the moral authority of Nobel laureate Heymans that they allowed him to organise relief campaigns for the population without interference. Jules Bordet, in turn, cunningly took advantage of his newfound fame to raise funds from the Rockefeller Foundation. The Swedish recognition also opened doors for the other laureates. They were asked to join prestigious international councils, advisory bodies and academies as honorary members or chairs.

The aura of the Nobel Prize also reflects on the institution with which the laureate is associated. Professor André de Schaepdrijver, for instance, described how the Physiological Institute grew into 'a Mecca of experimental physiology' after the recognition of its director Heymans: an institute with a glowing name that looked good on the CV of ambitious researchers. Christian De Duve founded the International Institute of Cellular and Molecular Pathology in the year of his award, of which he also became the first president. Because of its famous founder, the institute met with immediate success. Some laureates also eagerly used their awards themselves to talk their parent institution into the limelight. In his acceptance speech, for example, Heymans stated that his laureate position would provide the newly Dutchified University of Ghent with an 'international honour of unquestionable value'. Heymans' hopeful prediction was not without foundation. Like his father, Ghent's rector Jan Frans Heymans, junior was a great advocate for the Dutchification of education. Prigogine, for his part, in an autobiographical note on the occasion of his prize celebration, did not fail to highlight the crucial contribution of the Brussels School of Thermodynamics. Consequently, he was the main administrator of it...

As is tradition, Englert also seems intent on mobilising his sudden fame for his projects and convictions. He has already raised the issue of the publication pressure that young researchers are under today. He also suggested changing the name of the Higgs particle to Brout-Englert-Higgs particle. In addition, Englert still continues to lend his cooperation to the Interuniversity Attraction Pool "Fundamental Interactions". Will the nobled scientist, like his illustrious predecessors, see his famous name open new doors? An incident at the anniversary party of the Fund for Scientific Research already marks out the boundaries of noble fame: the prize-winning physicist made his way towards the cloakroom under the flashing light of cameras. He had to give his name there. The reception lady misunderstands. Her finger glides slowly along her list of names. It takes a bit long. 'E-N-G-L-E-R-T,' the laureate finally spells out to her. A silence follows, whereupon she hesitantly and slightly blushingly repeats: 'E-N-G-E-R-D? (a dutch word that means as much as "creep")'

|}

- Jump up ↑ Videofragment: Minister Ingrid Lieten feliciteert Englert..

- Jump up ↑ Belgium had already won the Nobel Peace Prize three times and the Nobel Prize for Literature once.

- Jump up ↑ The Nobel Prize was established in 1901. The first Nobel Prize in science for a Belgian was thus awarded after former Belgian minister of state Auguste Beernaert won a Nobel Peace Prize in 1909.

- Jump up ↑ "Prize motivation" on www.nobelprize.org, consulted 04/10/2018.

- Jump up ↑ See "Average age of all Nobel Laureates during the past century."

- Jump up ↑ Manifestations organisées en l’honneur de M. Jules Bordet, Professeur à l’université de Bruxelles, à l’occasion de l’attribution qui lui a été faite du prix Nobel de médecine pour 1920, p. 2.

- Jump up ↑ Idem.

- Jump up ↑ Idem, p27.

translation: ["You are its agent, dear Master, what shall I say, you are its glory and its crown!"] - Jump up ↑ www.ulb.be/nobel