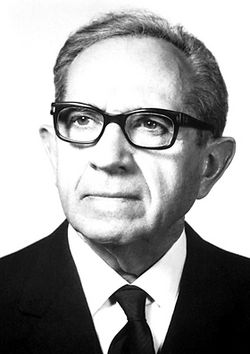

Claude, Albert (1898-1983)

Physician, microbiologist and Nobel Prize winner, born in Longlier (Neufchâteau) on 23 August 1898 and died in Elsene (Ixelles) on 23 May 1983.

Contents

[hide]Biography

Albert Claude was born in Longlier on 23 August 1898. His mother died of cancer when he was 7 years old. The family moved to Athus, in the German-speaking community. The young Albert left school at the age of 12 to work as an apprentice in the Athus Grivegné factory. Here he obtained the diploma of industrial draughtsman and worked in an industrial drawing office. In 1916 he joined the British Intelligence Service. He was holder of the British War Medal and the Médaille Interalliée. He was also the subject of a citation on the order of the day, signed by Winston Churchill who was then "Minister of State for War."[1]

He took and passed the entrance exam for the Ecole des Mines in 1921. His good fortune, however, was a 1922 ministerial decree which allowed ex-combatants to start university studies without a secondary school degree. He chose the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Liège. From the very beginning of his studies, he was involved in research. He worked in the laboratory of Désiré Damas, professor of zoology, where he studied the large collection of animal specimens. He then worked in the physiology laboratory run by Henri Frédéricq. This is where he met Marcel Florkin.

In 1928, he was awarded a doctorate in medicine, surgery and obstetrics.[2] He started to work in Louis Derlez's laboratory, where he, during his doctorate, had conducted research on the fate of S-37 cells transplanted into the subcutaneous tissues of young and adult rats and into the brains of adult rats.[3]

He spent the winter of 1928-1929 with this travel grant in Berlin: first at the Institut für Krebsforschung and then at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institut.[4] Afterwards he returned to Belgium and won a grant from the C.R.B (later BAEF) to travel to America. He went to work at the Rockefeller Institute, where he worked as a researcher for 20 years. He also obtained dual nationality.

In 1949, he accepted the ULB's invitation to become director of the Jules Bordet Institute.[5] At this institute he founded a laboratory for experimental cytology and cancerology. At the same time, he was appointed professor at the Faculty of Medicine of the ULB but taught no courses.[6] In 1972 he was admitted to emeritus status. He then moved to the UCL, where he was offered the directorship of the Laboratory of Cell Biology. It was here that he received the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 1974.[7]

Claude was elected corresponding member of the Royal Academy of Belgium on 3 June 1972. He was an honorary member of the Académie royale de médecine de Belgique, of the Koninklijke Vlaamse Academie voor Geneeskunde and of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. He was a foreign member of the Académie nationale de Paris. He was also an associate member of the Institut de France. Besides the Nobel Prize, Claude won a whole series of other awards. He received the Baron Holvoet Prize (NFWO) in 1965, the L.G. Horwitz Prize (Columbia University) in 1970 and the Paul Ehrlich and Ludwig Darmsttaedter Prize in 1974.

In 1955, he held the Francqui Chair at the University of Liège. He was visiting professor at the University of Pennsylvania (1967-1969), at John Hopkins University (1970-1972) and at the University of California (1970-1978).

He received honorary doctorates from the universities of Modena, Brno, Liège, Leuven, Ghent and from the Rockeffeler University.[8] He was also awarded the Grand Cross in the Order of Leopold II.[9]

Works

Albert Claude's medical studies at the University of Liège had as their main interest the analysis of the causes of cancer. In New York, he tried to isolate the carcinogenic origin of the Rous-sarcoma.

Thanks to the ultracentrifuges of the Rockefeller Institute, Claude was able to develop cell fractionation protocols and to demonstrate the existence of cytoplasmic granules of different sizes. Already at a relatively slow centrifuge speed, the mitochondria, which play a role in the energy metabolism of the cell, sedimented as well as various membrane fragments.

By using much faster centrifugal speeds, Claude was able to distinguish between larger and smaller particles, the so-called 'microsomes'. Initially, the latter were considered to be the carcinogens. The biochemical analysis revealed a composition of proteins, nucleic acids and phospholipids. Claude also showed that these granules could be 'inactivated' by ultraviolet rays, the spectrum of which coincided with the absorption spectrum of these rays by the nucleic acids. But control experiments with healthy tissues soon revealed the existence of identical particles, thus ruling out the specific role of microsomes in oncogenesis.[10]

Christian de Duve at the UCL and Albert Claude at the ULB both played an important role in the development of institutes that integrated both fundamental and medical research and were populated with scientists mastering the most advanced molecular techniques. The Institute of Cellular Pathology (ICP) and the Institut Bordet quickly built up an international reputation. Albert Claude and Christian de Duve's work was jointly awarded the 1974 Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine, a prize they shared with their American colleague George Palade.[11]

History of science

Claude was also the author of two historical publications entitled: Fractionation of mammalian liver cells by differential centrifugation. It dealt on the history of the centrifuge as a scientific technique.[12]

Publications

- A list with publications can be found in: Brachet, Jean, "Albert Claude", In: Annuaire ARB, jaargang 1988, p. 122-135.

Bibliography

- Brachet, Jean, "Albert Claude", In: Annuaire ARB, 1988, p. 93-122.

- De Duve, Christiaan, "Albert Claude", In: Nouvelle Biographie Nationale, vol. 4, 1997, p. 60-64.

- Denis, Thieffry, "De fundamentele biologie: van het organisme tot de cel, van de molecule tot het ecosysteem", in: Robert Halleux, Geert Vanpaemel, Jan Vandersmissen en Andrée Despy-Meyer (red.), Geschiedenis van de wetenschappen in België 1815-2000, Brussel: Dexia, 2001, vol. 2, p. 206-207.

Notes

- Jump up ↑ De Duve, Christiaan, "Albert Claude", In: Nouvelle Biographie Nationale, vol. 4, 1997, p. 60.

- Jump up ↑ Brachet, Jean, "Albert Claude", In: Annuaire ARB, jaargang 1988, p. 97-98.

- Jump up ↑ De Duve, Christiaan, "Albert Claude", In: Nouvelle Biographie Nationale, vol. 4, 1997, p. 61.

- Jump up ↑ "Autobiography of Albert Claude, Summarized Civic and Academic Status", In: Florilège des Sciences en Belgique, vol. 2, Brussel, 1980, ARB, p. 34.

- Jump up ↑ De Duve, Christiaan, "Albert Claude", In: Nouvelle Biographie Nationale, vol. 4, 1997, p. 61.

- Jump up ↑ Brachet, Jean, "Albert Claude", In: Annuaire ARB, jaargang 1988, p. 103.

- Jump up ↑ De Duve, Christiaan, "Albert Claude", In: Nouvelle Biographie Nationale, vol. 4, 1997, p. 61.

- Jump up ↑ Brachet, Jean, "Albert Claude", In: Annuaire ARB, jaargang 1988, p. 121-122.

- Jump up ↑ De Duve, Christiaan, "Albert Claude", In: Nouvelle Biographie Nationale, vol. 4, 1997, p. 61.

- Jump up ↑ Denis, Thieffry, "De fundamentele biologie: van het organisme tot de cel, van de molecule tot het ecosysteem", In: Robert Halleux, Geert Vanpaemel, Jan Vandersmissen en Andrée Despy-Meyer (red.), Geschiedenis van de wetenschappen in België 1815-2000, Brussel: Dexia, 2001, vol. 2, p. 206.

- Jump up ↑ Denis, Thieffry, "De fundamentele biologie: van het organisme tot de cel, van de molecule tot het ecosysteem", In: Robert Halleux, Geert Vanpaemel, Jan Vandersmissen en Andrée Despy-Meyer (red.), Geschiedenis van de wetenschappen in België 1815-2000, Brussel: Dexia, 2001, vol. 2, p. 207.

- Jump up ↑ De Duve, Christiaan, "Albert Claude", In: Nouvelle Biographie Nationale, vol. 4, 1997, p. 62.