Oratio De Utilitate Studii Historiae Scientiarum Physicarum (1819)

On June 8 1821, Franz-Peter Cassel, professor of botany and the second rector of the newly founded State University of Ghent, died. Notable, however, was his 1819 rectoral address in which he made an ardent plea for the study of the history of science.

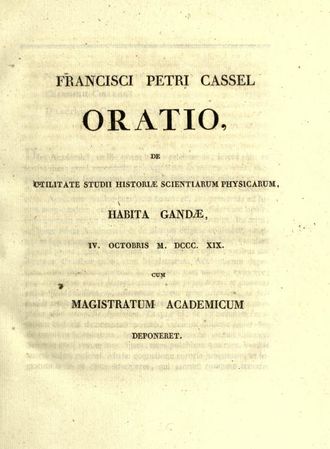

In the state universities founded by William I, a rector had to be appointed each year, elected alternately from each of the four faculties. In 1818, it was the botanist Franz-Peter Cassel's (1784-1821) turn. The task of a rector was rather administrative, but he was also expected to deliver a public speech at the end of his rectorship. Usually those speeches dealt with developments within the rector's field of study. Cassel, however, chose a broader and more philosophical subject. On Oct. 4, 1819, he delivered a speech in latin on the usefulness of the study of natural sciences. The text was published soon after in French translation in the Annales belgiques des sciences, arts et littératures.

In doing so, Cassel warned of another, more current threat to the sciences, namely that they are viewed by many as a form of entertainment. Physical experiments or natural history collections are viewed purely as entertainment or curiosities, "a view that is less rare than one might think". What is the point of science? Indeed, the question was not easy to answer because its immediate practical use was not always apparent. Science must be practised for its own sake, Cassel believed. It has its intrinsic and independent rights. Its practical usefulness will follow naturally for those who cultivate it. "The first scholar to investigate the properties of conic sections had no idea that projectiles followed a parabolic trajectory, and that celestial bodies moved on elliptical orbits." Cassel did not doubt it: "Il n'y pas de doute que les découvertes des sciences physiques ne puissent avoir la plus heureuse influence sur l'amélioration de l'ordre social et l'augmentation du bonheur public." [6] It was precisely the history of science, through its long succession of ideas and applications, that could show how the study of nature always led to the advancement of culture and the increase of prosperity. In the historical consideration of the sciences, it was possible to find the seeds of what the future would bring.

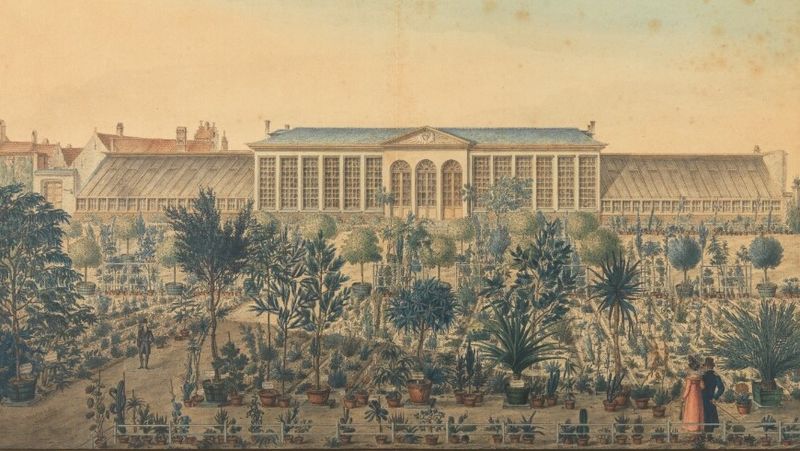

At the end of his speech, Cassel addressed William I, "le meilleur des monarques"[7], who had founded Ghent University. The role of enlightened monarchs on the progress of science had already been sufficiently demonstrated in history. Cassel was happy to point to William I's energetic policy of supporting the sciences in the construction and acquisition of scientific collections, physical and chemical instruments, botanical gardens and anatomical theatres. The day was incidentally given special splendour by the laying of the foundation stone of the Ghent Aula by baron Falck, William I's plenipotentiary minister .

Whether Cassel's plea for the history of science found much support among his listeners cannot be ascertained. Cassel did not play on patriotic sentiments. He did mention a reasonable number of scholars from the Low Countries: Swammerdam, Ruysch, Schrader, Huygens, Boerhaave, Vesalius, Van Helmont and Dodoens, but without making any particular connection to the current state of the United Kingdom of the Netherlands. Possibly his speech did impress one of the students who graduated from Ghent University in 1819 and who, like Cassel, had taken a keen interest in the history of science: Adolphe Quetelet.

For Cassel, there was no follow-up to his speech. In the spring of 1820, he had to stop teaching for health reasons. He died the following year, on 8 June 1821.

- F.P. Cassel, “Oratio de Utilitate studii historiae scientiarum physicarum, habita Gandae, IV. Octobris M.DCCC.XIX.” Annales Academiae Gandavensis (1819), 1-15.

- F.P. Cassel, "Sur l’étude de l’histoire des sciences physiques,” Annales belgiques des sciences, arts et littératures, 4 (oktober 1819), p. 251-267. De vertaling werd gemaakt door Louis Vincent Raoul (1770-1848), hoogleraar in de Letterenfaculteit van de Gentse universiteit.

Notes

- ↑ "learn the sciences well, remove the prejudices that hinder their progress, and expand the field of natural philosophy."

- ↑ burning with the sole desire to know nature

- ↑ "It is there, in the history of science, that we learn both what nature can do to create genius, and what a genius can do to reveal nature; for what sustains, what strengthens this admirable patience of naturalists, is the hope of discovering the general laws of nature; a discovery that reason alone cannot promise itself, but in which, when observation makes it happen, it finds the sweetest of joys."

- ↑ "he stopped working and living at the same time."

- ↑ "We are no longer in the century of secrets and mysteries; the temple of science is open to all who are curious. [...] This way of no longer considering ideas, new inventions, as a private property, but as a common good, a part of the public domain, has something more worthy of a philosopher, more appropriate to the philanthropic spirit that should animate scholars. And indeed truth can cause no harm; it is not science that is to be feared, but ignorance; it is not in broad daylight that one runs into danger, but in the darkness."

- ↑ "There is no doubt that the discoveries of the physical sciences can have the happiest influence on the improvement of social order and the increase of public happiness."

- ↑ "the best of Monarchs"